Heart Rate Variability Meaning and Measurements (1 Hour)

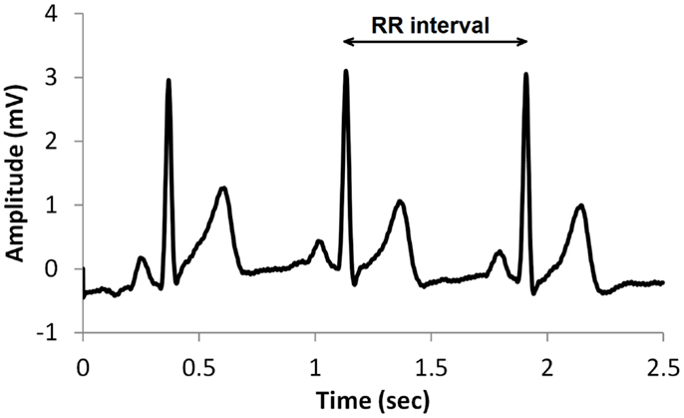

"HRV is the organized fluctuation of time intervals between successive heartbeats defined as interbeat intervals" (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

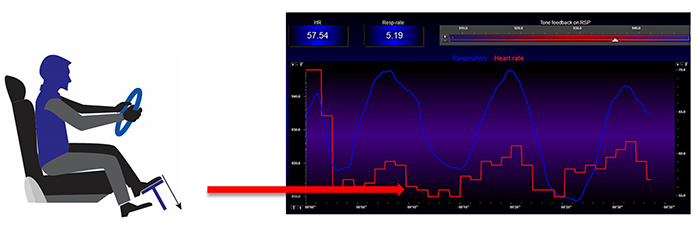

The oscillations of a healthy heart are complex. HRV indexes how efficiently we mobilize and utilize limited self-regulatory resources to maintain homeostasis. HRV plays a vital role in regulatory capacity, executive functions, health, and performance. A healthy heart can rapidly adjust to sudden challenges due to the cooperation of interlocking and better-calibrated control systems. HRV is crucial to health, performance, and resilience. Behavioral interventions like aerobic exercise, healthy breathing, compassion, and mindfulness meditation are powerful strategies for increasing HRV. Graphic © Maridav/Shutterstock.com

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses Heart Rate Variability Meaning and Measurements (2 hours) and covers HRV, Time-Domain Measurements, Frequency-Domain Measurements, and Assessment.

This section covers The Meaning of HRV, The Sources of HRV, Factors that Influence HRV, Correlates of Low and Normal HRV, The Benefits of HRV, and Heart-Brain Interactions.

A. The Meaning of HRV

Heart rate is the number of heartbeats per minute. Graphic © Crdjan/Shutterstock.com.

Elevated HR Is Associated with Dementia and Cognitive Decline

Imahori et al. (2021) conducted a cohort study of 2147 adults ≥ 60 who were free of dementia when they entered the study. Resting heart rates (RHR) ≥80 (compared with 60-69 bpm) were associated with a greater risk of dementia and more rapid cognitive decline, independent of cardiovascular disease (CV).Elevated HR Limits HRV

HR is important because a high rate can reduce heart rate variability (HRV), the changes in the time intervals between consecutive heartbeats (Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology, 1996). Graphic © arka38/Shutterstock.com.

Listen to a mini-lecture on a Heart Rate Variability Overview © BioSource Software LLC.

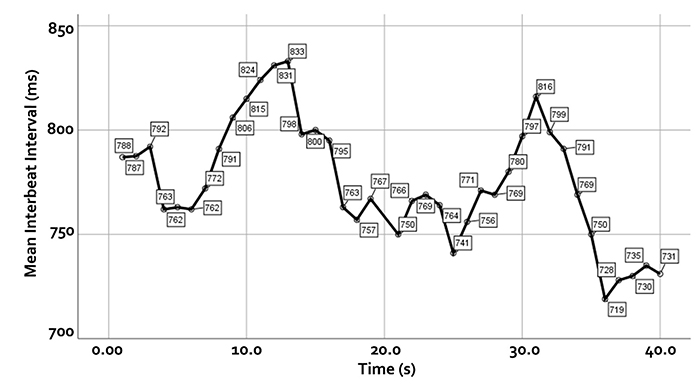

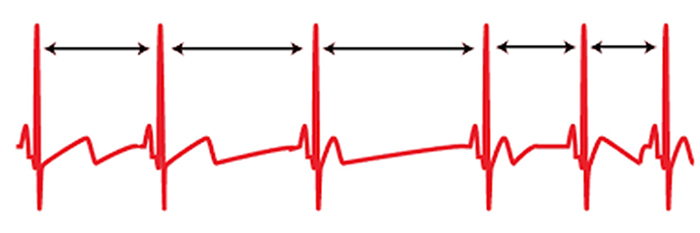

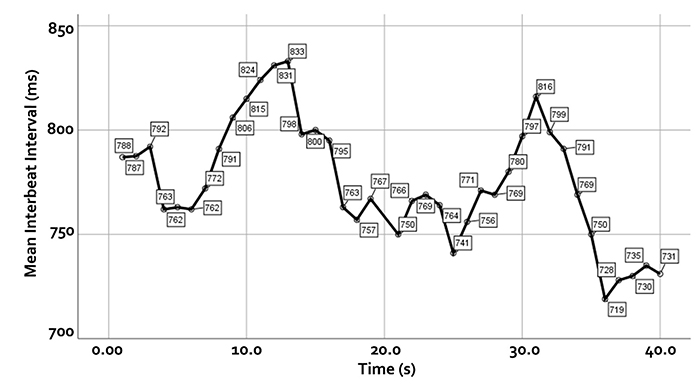

We measure the time intervals between successive heartbeats in milliseconds. Graphic courtesy of Dick Gevirtz.

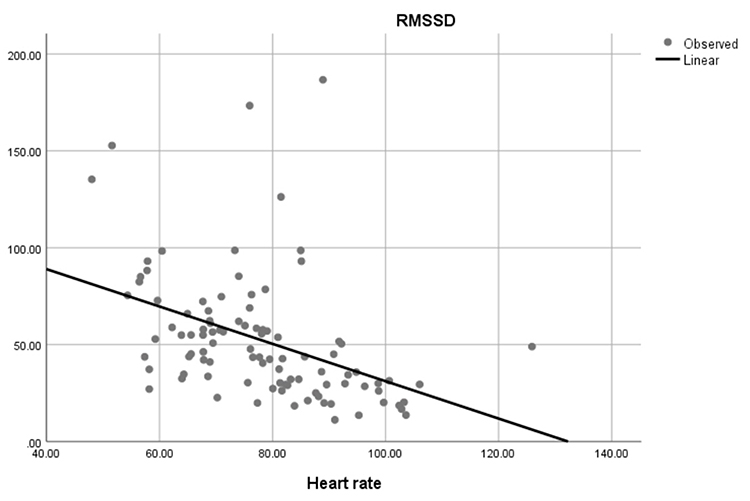

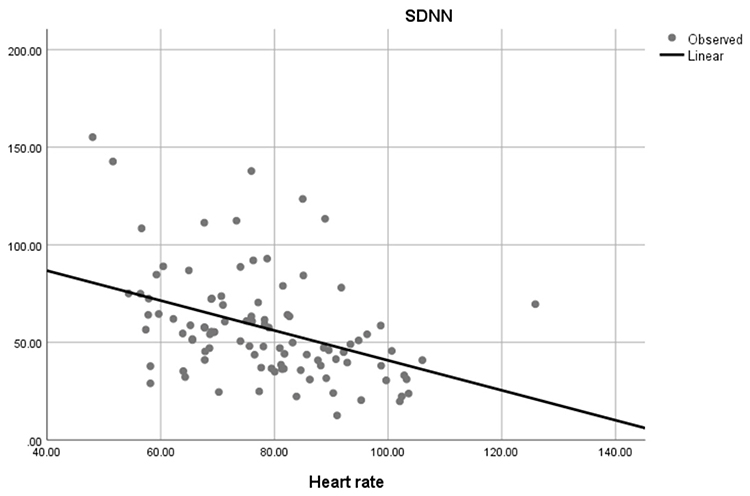

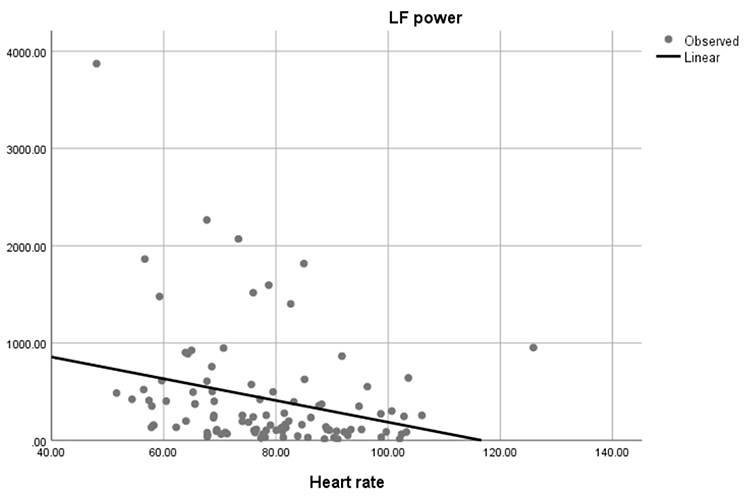

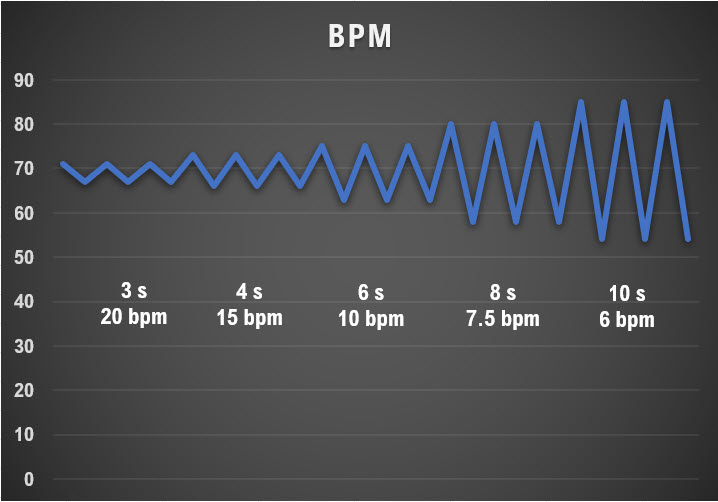

Faster HRs reduce the time between successive beats and the opportunity for interbeat intervals (IBIs) to vary. Faster HRs lower HRV. Resting HRs that exceed 90 bpm are associated with an elevated risk of mortality (Zhang, Shen, & Qi, 2016). The next three scatterplots show an inverse relationship between HR and three widely used HRV metrics: RMSSD, SDNN, and low-frequency power.

Conversely, the slower HRs seen in endurance sports like trail running increase the time between adjacent heartbeats and the chance for IBIs to vary. This raises HRV. This phenomenon is called cycle length dependence (McCraty & Shaffer, 2015). Graphic © Maridav/Shutterstock.com.

Typical non-athlete HRs are 60-80 bpm. Athletes may have HRs between 40-60 bpm (Khazan, 2019). Graphic © Jacob Lund/Shutterstock.com.

Dr. Gevirtz explains HRV © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. You can enlarge this video by clicking on the bracket icon at the bottom right of the screen. When finished, click on the ESC key.

A Healthy Heart Is Not a Metronome

A healthy heart is not a metronome.

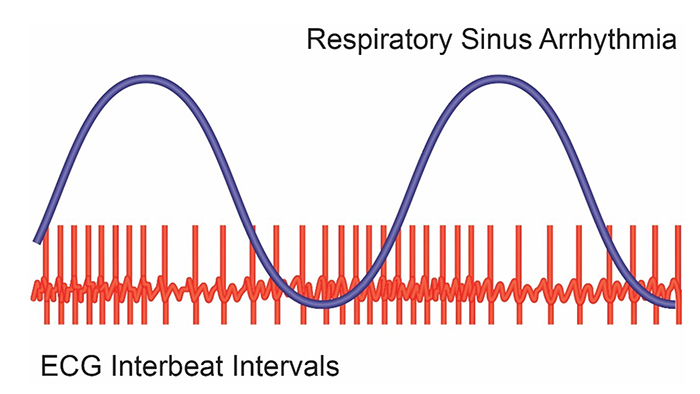

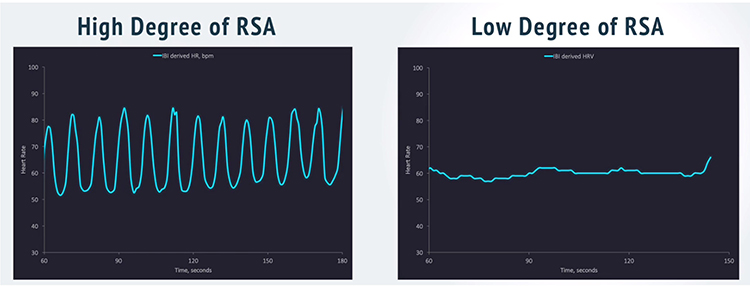

When the time intervals between heartbeats significantly change across successive breathing cycles, this shows that the cardiovascular center can effectively modulate vagal tone.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Why Is Heart Rate Variability Important? © BioSource Software LLC.

The record below shows healthy variability. The time intervals between successive heartbeats differ.

In contrast, this record shows no variability since the IBIs are identical. This display could represent a heart driven by a pacemaker or a heart that needs one.

"The complexity of a healthy heart rhythm is critical to the maintenance of homeostasis because it provides the flexibility to cope with an uncertain and changing environment...HRV metrics are important because they are associated with regulatory capacity, health, and performance and can predict morbidity and mortality" (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

Check out the YouTube video HRV Training and its Importance. Graphic © Axynia/Shutterstock.com."... HRV is associated with executive function, regulatory capacity, and health... Cardiac vagal control indexes how efficiently we mobilize and utilize limited self-regulatory resources during resting, reactivity, and recovery conditions" (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

The modulation of vagal tone helps maintain the dynamic autonomic balance critical to cardiovascular health. Autonomic imbalance due to deficient vagal inhibition is implicated in increased morbidity and all-cause mortality (Thayer, Yamamoto, & Brosschot, 2010).HRV appears to index autonomic functioning, BP, neurocardiac functioning, digestion, oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, vascular tone (diameter of resistance vessels), and possibly facial muscle regulation (Gevirtz et al., 2016). HRV reflects the vagal contribution to executive functions, affective control, and social self-regulation (Byrd et al., 2015; Laborde et al., 2017; Mather & Thayer, 2018).

Vagal tank theory (Laborde et al., 2018) argues that vagal traffic to the heart indicates how efficiently we mobilize and use scarce self-regulatory resources.

The Sources of HRV

HRV is produced by interacting regulatory mechanisms that operate on different time scales (Moss, 2004). Circadian rhythms, core body temperature, and metabolism contribute to 24-hour HRV recordings, representing the "gold standard" for clinical HRV assessment. The parasympathetic, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems produce short-term (e.g., 5-minute) HRV measurements.

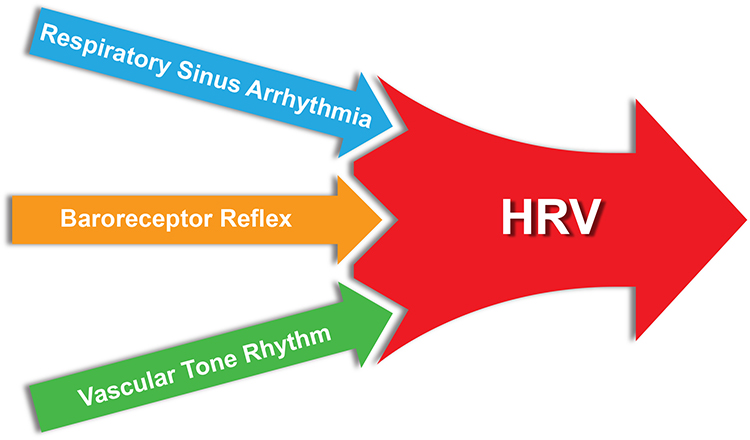

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, the baroreceptor reflex, and the vascular tone rhythm are the most important sources of HRV (Hayano & Yuda, 2019; Vaschillo et al., 2002).

Listen to a mini-lecture on Sources of Heart Rate Variability © BioSource Software LLC.

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), HR speeding and slowing across each breathing cycle, is the primary and entirely parasympathetic source of HRV (Gevirtz, 2020). Graphic adapted from Elite Academy.

Inhalation partially disengages the vagal brake, speeding HR. This is purely parasympathetic. Graphics inspired by Dick Gevirtz.

Exhalation reapplies the vagal brake, slowing HR.

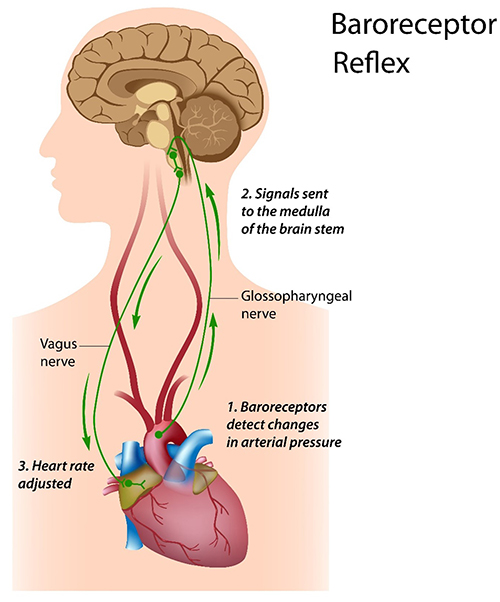

The baroreceptor reflex, which exerts homeostatic control over acute BP changes, is the second most important and entirely parasympathetic source of HRV (Gevirtz, 2020).

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Baroreceptor Reflex © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Alila Sai Mai/Shutterstock.com.

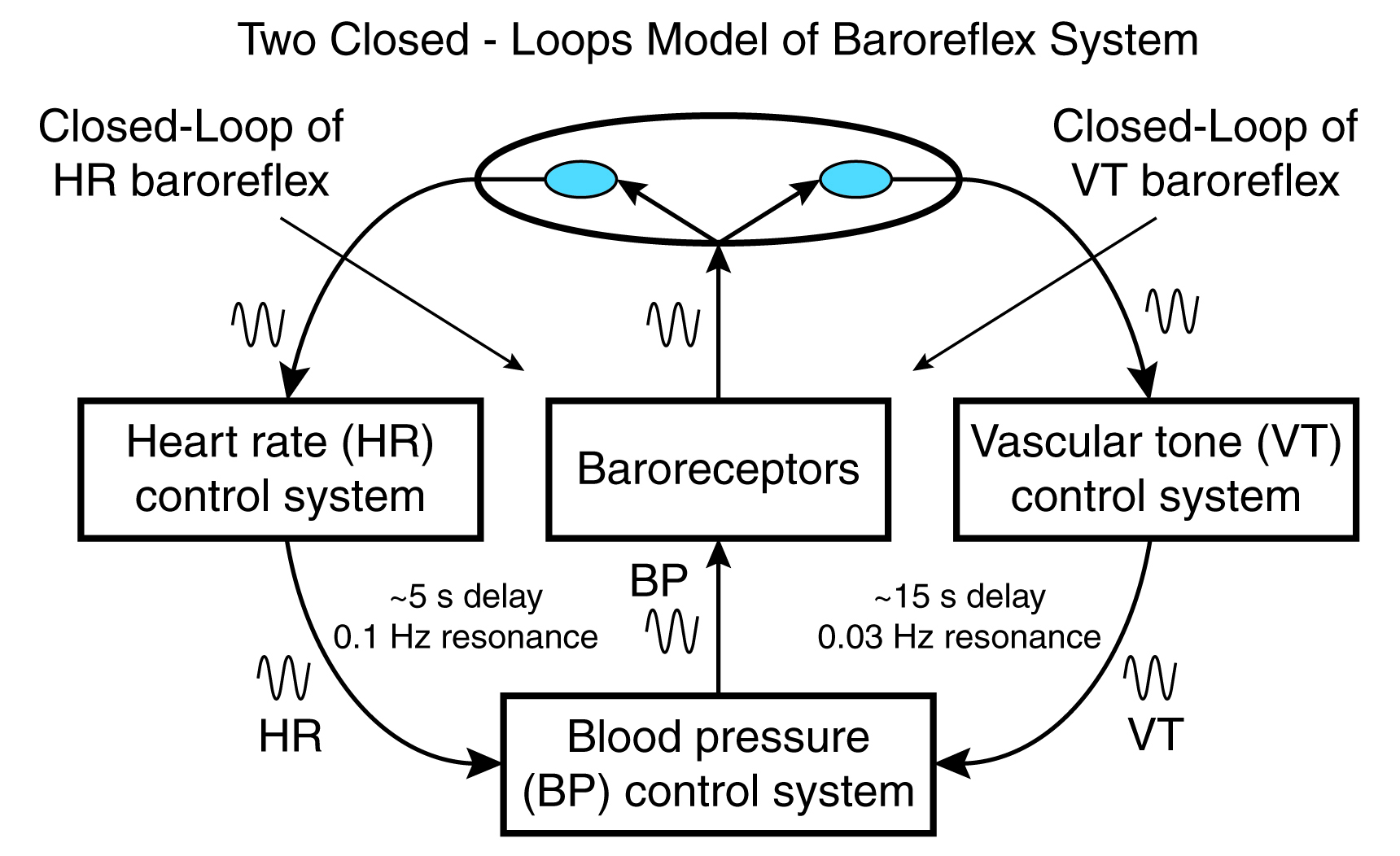

The vascular tone (VT) control system with a 15-second delay and 0.03 Hz resonance is the third source of HRV. Vaschillo and colleagues (2002) proposed that there is a VT baroreflex closed-loop that works in concert with HR baroreflex closed-loop to regulate blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR). Graphic adapted from Vaschillo.

Factors That Influence HRV

Critical factors that influence HRV include HR, resonance, respiration rate, and depth.

HR Limits HRV

We discussed cycle length dependence earlier. Faster HRs decrease the opportunity for IBIs to vary in length, whereas slower HRs increase the chance of beat-to-beat differences.Resonance

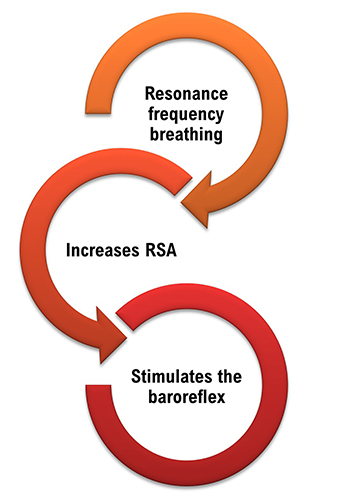

Slow-paced breathing increases RSA by stimulating the baroreceptor system at its unique resonance frequency (RF; ~ 0.1 Hz). The RF is caused by the delay in the baroreflex (Lehrer et al., 2004). Before HRVB, respiration and the baroreflex are usually out of phase resulting in weak resonance effects.

Visualize pushing a child on a swing. There is a single frequency that moves the child the highest. The best pushing rate is analogous to the RF (Khazan, 2020). Graphic © Billion Photos/Shutterstock.com.

Resonance is simple physics (Lehrer, 2020). A bell struck by a Buddhist monk for prayer time resonates after the initial strike. Graphic © Amith Nag/Shutterstock.com.

Dr. Lehrer explains resonance © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

The baroreflex system exhibits resonance since it is a feedback system with a fixed delay. Inertia due to blood volume in the vascular tree accounts for most of this delay.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Resonance © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Shot4Sell/Shutterstock.com.

Taller people and men have lower resonance frequencies than women and shorter people because they have larger blood volumes.

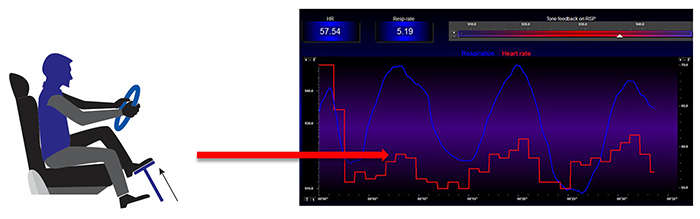

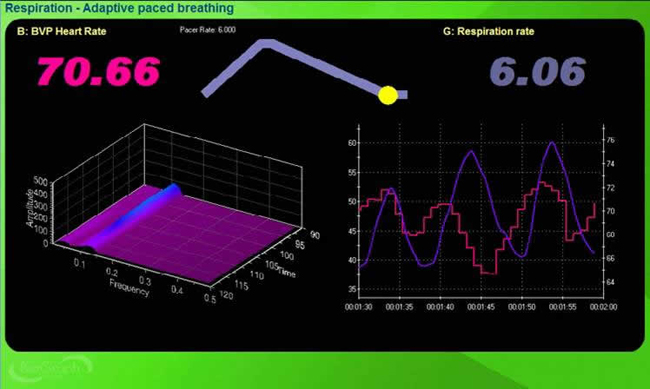

When clients breathe at their RF, HR and respiration are in perfect phase (0°); their peaks and valleys coincide.

Listen to a mini-lecture on the RF © BioSource Software LLC.

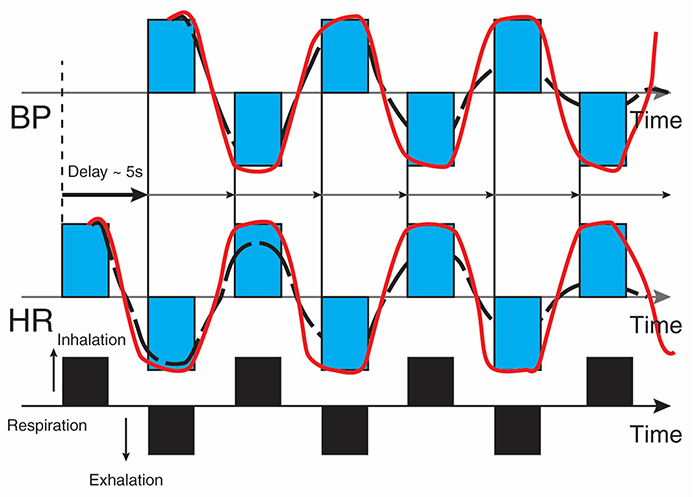

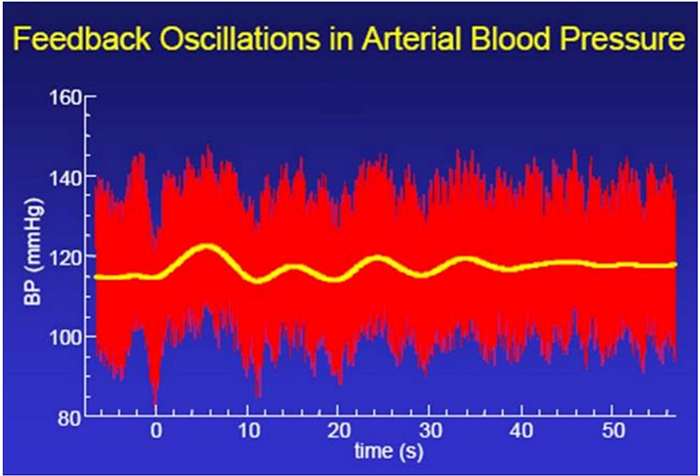

Resonance frequency breathing also modulates BP changes since HR and BP oscillations are 180° out of phase (DeBoer, Karemaker, & Strackee, 1987; Vaschillo et al., 2002). Graphic adapted from Evgeny Vaschillo.

Revised caption: The bottom line represents respiration. A rising black bar is inhalation, and a falling black bar means exhalation. The following lines represent HR and BP. This diagram allows us to see the changes in HR and BP produced by breathing. Starting at the bottom left, inhalation speeds the heart, and about 5 seconds later, BP falls. During exhalation, the heart slows, and about 5 seconds later, BP increases.

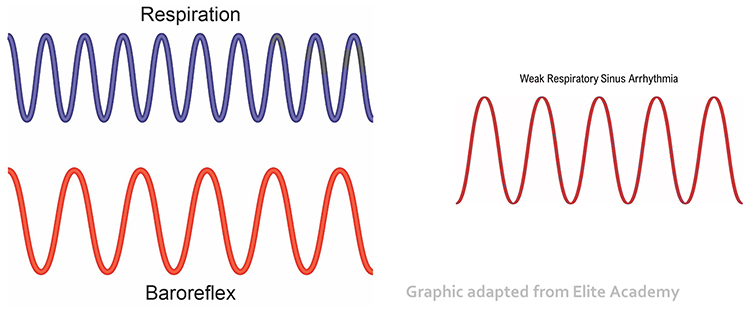

Before HRVB, respiration and the baroreflex are usually out of phase resulting in weak resonance effects. Graphic adapted from Elite Academy.

Listen to a mini-lecture on RF Breathing © BioSource Software LLC.

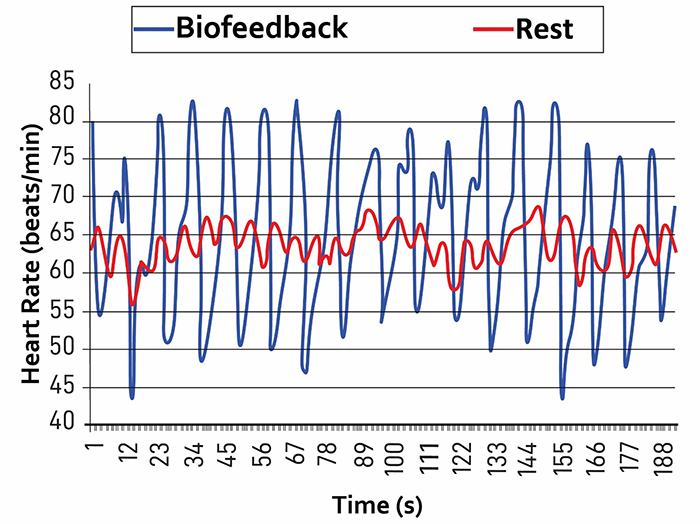

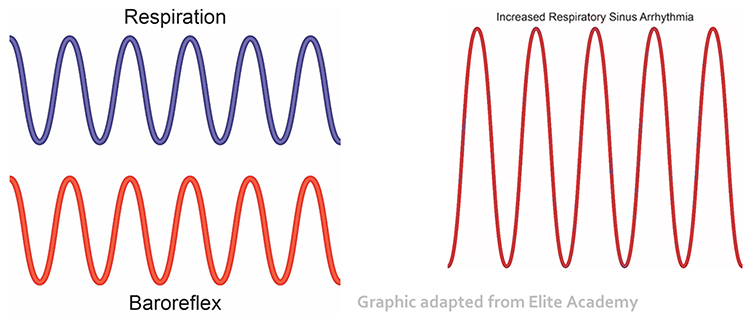

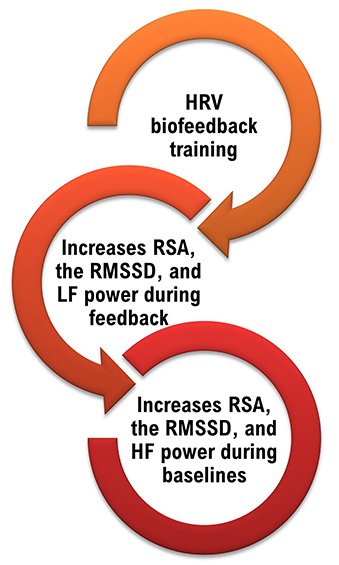

HRV biofeedback training slows breathing to the baroreflex’s rhythm, which aligns these processes and significantly increases resonance effects. Graphic adapted from Elite Academy.

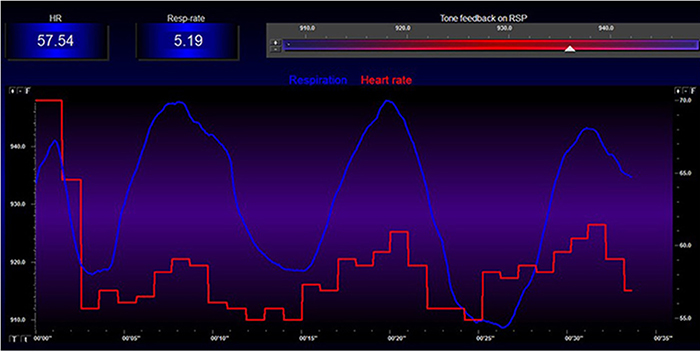

Slowing breathing to rates between 4.5-6.5 bpm for adults and 6.5-9.5 bpm for children increases RSA (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). Increased RSA immediately “exercises” the baroreflex without changing vagal tone or tightening BP regulation. Those changes require weeks of practice. HRV biofeedback can increase RSA 4-10 times compared to a resting baseline (Lehrer et al., 2020b; Vaschillo et al., 2002).

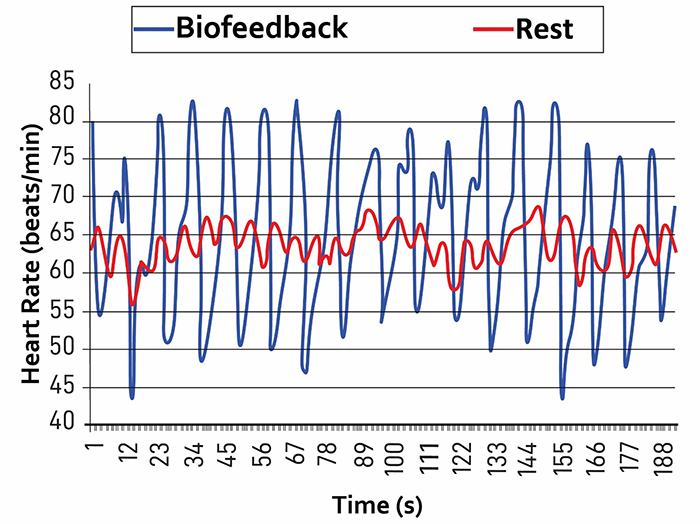

Listen to a mini-lecture on Increased RSA © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic adapted from Gevirtz et al., 2016.

Caption: The red waveform shows HR oscillations while resting without breathing instructions or feedback. The blue waveform shows HR oscillations with HRV biofeedback and breathing from 4.5-6.5 bpm.

Listen to a mini-lecture on HRV Changes During and After Training © BioSource Software LLC.

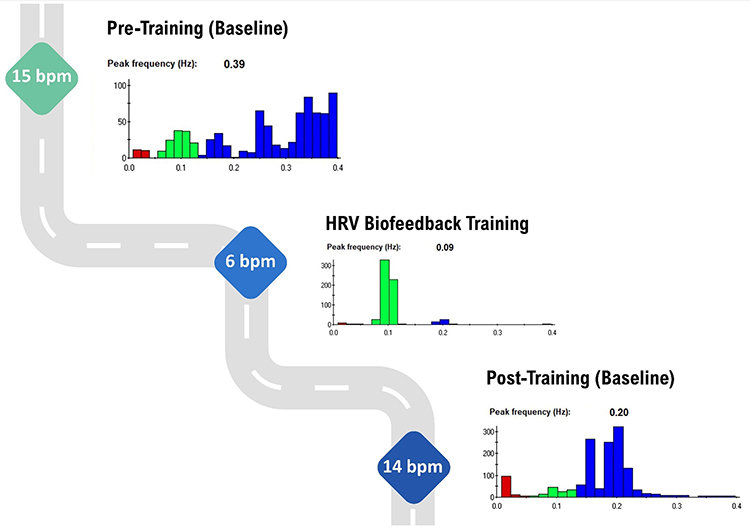

You can observe the effect of a breathing rate on RSA during paced breathing and select the rate that produces the largest HR oscillations. Adult breathing from 4.5-6.5 bpm shifts the ECG peak frequency from the high-frequency band (~0.20 Hz) to the cardiovascular system’s RF (~0.10 Hz). This more than doubles the energy in the low-frequency band of the ECG (0.04-0.15 Hz).

We train clients to increase low-frequency power and RSA so that high-frequency power and time-domain measures like the RMSSD will increase during baselines when breathing at typical rates (Lehrer, 2020).

Breathing Rate and Depth

RSA increases with greater respiratory depth (Hirsch & Bishop, 1981) and lowers respiration rate (Brown et al., 1993). The graphic below was adapted from Grossman and Kollai (1993). RSA, shown as a change in heart rate from inhalation to exhalation, increases as the respiration rate approaches 6 bpm.

Correlates of Low and Normal HRV

Heart Rate Variability Is a Marker for Disease and Adaptability

Since a healthy cardiovascular system integrates multiple control systems, its overlapping oscillatory patterns are chaotic.Listen to a mini-lecture on Heart Rate Variability Is a Marker for Disease and Adaptability © BioSource Software LLC.

The double compound pendulum animation from Wikipedia shown below illustrates chaotic behavior. Slightly changing the pendulum's starting condition results in a radically different trajectory.

A healthy heart exhibits complexity in its oscillations and rapidly adjusts to sudden physical and psychological challenges due to its effective interlocking cardiac control systems. A healthy heart illustrates the concept of allostasis or the achievement of stability through change. In contrast, an aging or diseased heart shows noncomplex oscillations and ineffectively responds to sudden demands due to the breakdown of its control mechanisms (Lehrer & Eddie, 2013). Check out the YouTube video Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Biofeedback by Mark Stern.

Heart rate variability biofeedback is extensively used to treat various disorders (e.g., asthma and depression) and enhance performance in various contexts (e.g., sports; Gevirtz, 2013; Lehrer et al., 2020a; Tan et al., 2016).

Lehrer et al. (2020) observed that “…HRVB has the largest effect sizes on anxiety, depression, anger, and athletic/artistic performance and the smallest effect sizes on PTSD, sleep, and quality of life” (p. 109).

Although the final targets of these applications may differ, HRVB increases vagal tone (Vaschillo et al., 2006) and stimulates the negative feedback loops responsible for homeostasis (Lehrer & Eddy, 2013).

Whereas HRV is desirable, BP variability can endanger health. We require BP stability under constant workloads (Gevirtz, 2020). Graphic courtesy of Dick Gevirtz.

Reduced HRV Is Associated with Disease and Loss of Adaptability

In the early 1960s, researchers found that changes in HRV preceded fetal distress (Hon & Lee, 1963).Listen to a mini-lecture on Reduced HRV Is Associated with Disease and Loss of Adaptability © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © SciePro/Shutterstock.com.

Reduced HRV is associated with vulnerability to physical and psychological stressors and disease (Lehrer, 2007).

Graphic © Arseniy Krasnevsky/Shutterstock.com.

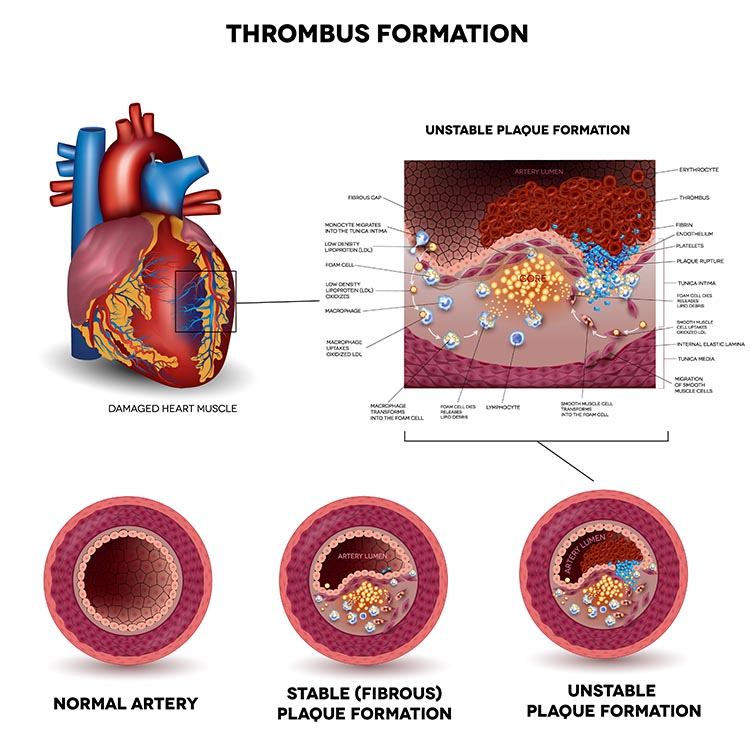

Prospective studies have shown that decreased HRV is the strongest independent predictor for the progression of coronary atherosclerosis (McCraty & Shaffer, 2015). Graphic © Tefi/Shutterstock.com.

Low HRV is a marker for cardiovascular disorders, including hypertension, especially with left ventricular hypertrophy; ventricular arrhythmia; chronic heart failure; and ischemic heart disease (Bigger et al., 1995; Casolo et al., 1989; Maver, Strucl, & Accetto, 2004; Nolan et al., 1992; Roach et al., 2004). Low HRV predicts sudden cardiac death, particularly due to arrhythmia following myocardial infarction and post-heart attack survival (Bigger et al., 1993; Bigger et al., 1992; Kleiger et al., 1987).

Depression in myocardial infarction (MI) patients increases mortality. Depressed patients are twice as likely as non-depressed individuals to have lower HRV (16% vs. 7%). Lower HRV is a strong independent predictor of post-MI death (Craney et al., 2001). HRVB might reduce anxiety and depression, which are associated with low vagal activity because it increases vagal tone. From Friedman’s (2007) perspective, the problem is not “a sticky accelerator.” HRVB may fix “bad brakes” (p. 186).

Reduced HRV may predict disease and mortality because it indexes reduced regulatory capacity, which is the ability to surmount challenges like exercise and stressors. Patient age may be an essential link between reduced HRV and regulatory capacity since both HRV and nervous system function decline with age (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014). Graphic © Maridav/Shutterstock.com.

Reduced HRV is also seen in disorders with autonomic dysregulation, including anxiety and depressive disorders, and asthma, and vulnerability to sudden infant death (Agelink et al., 2002; Carney et al., 2001; Cohen & Benjamin, 2006; Giardino, Chan, & Borson, 2004; Kazuma, Otsuka, Matsuoka, & Murata, 1997). Lehrer (2007) believes that HRV indexes adaptability and marshals evidence that increased RSA represents more efficient regulation of BP, HR, and gas exchange by synergistic control systems.

Dr. Lehrer explains how disease affects the normally chaotic ECG signal © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

The Benefits of Increased HRV

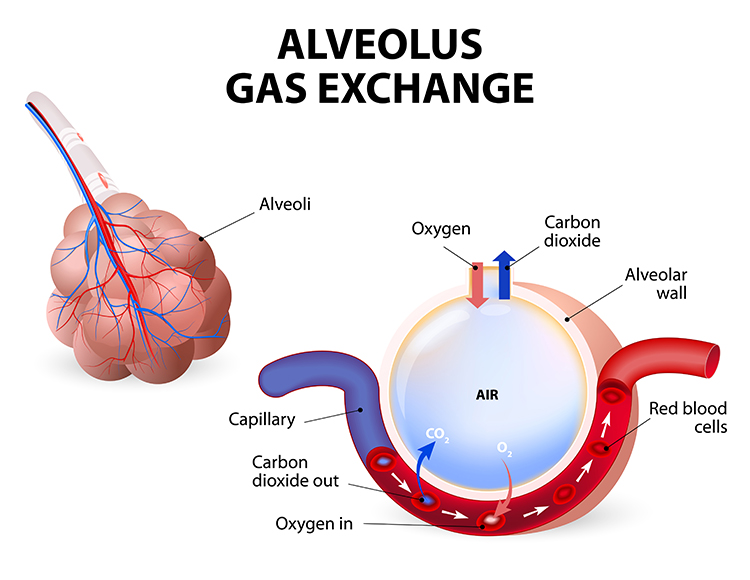

The core benefits of increased HRV are enhanced RSA, low-frequency band power, carbon dioxide and oxygen regulation, baroreflex gain and blood pressure (BP) regulation, modulation of immunity, and remodeling damaged hearts.

RSA

When clients breathe at their resonance frequency, HR and respiration are in perfect phase (0o); their peaks and valleys coincide. In adults, this frequency varies from 4.5-6.5 breaths per minute (Gevirtz, Lehrer, & Schwartz, 2016). When clients breathe at this rate, they “exercise” the baroreflex.Resonance frequency (RF) breathing amplifies the swings in HR produced by the baroreflex, increasing baroreflex gain and RSA. RF breathing also modulates blood pressure changes since HR and BP oscillations are 180o out of phase (DeBoer, Karemaker, & Strackee, 1987; Vaschillo et al., 2002).

Low-frequency Band Power

RF breathing shifts the peak frequency from the high-frequency band (~0.20 Hz) to the cardiovascular system’s RF (~0.10 Hz). RF breathing more than doubles the energy in the low-frequency band of the ECG (0.04-0.15 Hz). This corresponds to the Institute of HeartMath's concept of coherence, in which a client produces a "narrow, high-amplitude, easily visualized peak" from 0.09-0.14 Hz (Ginsberg, Berry, & Powell, 2010, p. 54; McCraty et al., 2009).

Regulation of Carbon Dioxide and Oxygen

The perfect phase relationship between HR and respiration rate results in the most efficient gas exchange and optimal oxygen saturation (Bernardi et al., 2001; Vaschillo, Vaschillo, & Lehrer, 2004; Yasuma & Hayano, 2004). Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

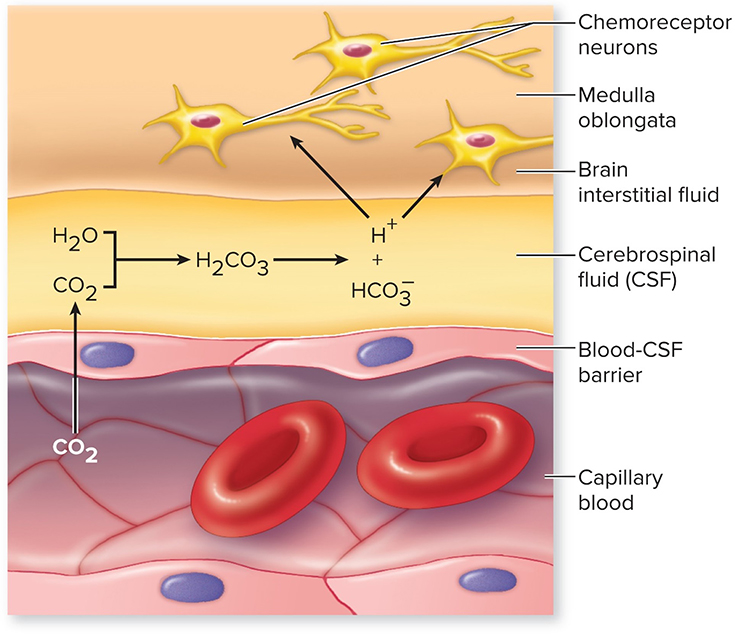

Resonance frequency training also improves oxygen regulation by increasing the sensitivity of chemoreceptors that detect oxygen and carbon dioxide. Graphic © McGraw-Hill.

Baroreflex Gain and BP Regulation

While HRV biofeedback training immediately produces large-scale RSA increases, months of practice can increase baroreflex gain when clients are not receiving feedback (Lehrer, 2013; Lehrer et al., 2003). Increased baroreceptor gain is analogous to a more sensitive thermostat. The body regulates BP more effectively. Graphic © Sean Locke Photography/Shutterstock.com.

Increased baroreflex gain means that the cardiovascular system produces large-scale HR increases and decreases when a client inhales and exhales. This, in turn, translates into greater HRV.

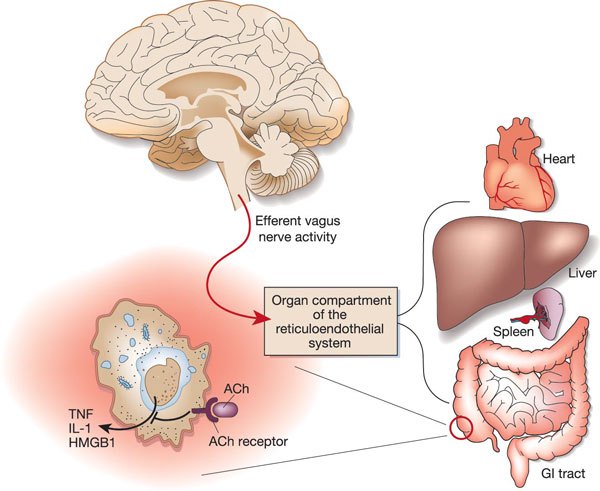

Modulation of Immunity

Like vagal nerve stimulation (VNS), resonance frequency breathing may also influence the parasympathetic cholinergic cytokine control system that modulates immunity through interleukins and interferons (Gevirtz, 2013; Tracey, 2007).The sensory vagus detects inflammation/infection via tissue necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1). The motor vagus signals descending neurons to release norepinephrine to spleen T cells, prompting these cells to release acetylcholine to macrophages to dampen inflammation (Schwartz, 2015).

Chronic inflammation is implicated in various disorders, including Alzheimer's, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, depression, and diabetes (Dhar, Lambert, & Barton, 2016; Poole, Dickens, & Steptoe, 2011). Graphic © arka38/Shutterstock.com.

Lehrer et al. (2010) demonstrated that subjects trained to breathe at their RF minimized the reduction of HRV, headache, and eye photosensitivity following an injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an inflammatory cytokine.

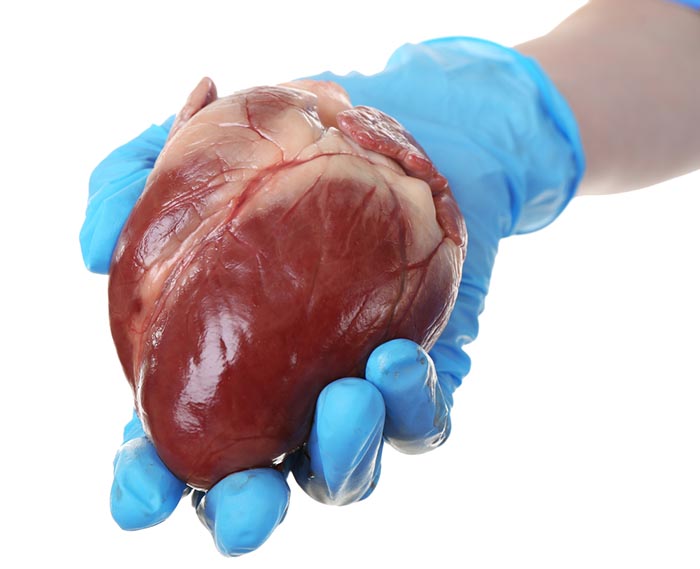

Remodeling Failing Hearts

Moravec and McKee (2013) reported preliminary evidence that HRV biofeedback may act like a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) to help remodel failing hearts.Examination of harvested hearts revealed that transplant candidates trained to slow their breathing down to 8-9 breaths per minute increased the numbers of β1 receptors on cardiac muscle fibers and cardiac muscle contraction in response to norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E). Graphic © Africa Studio/ Shutterstock.com.

HRV biofeedback for heart failure patients represents a paradigm shift. Instead of only targeting sympathetic activation, HRV biofeedback teaches patients to restore autonomic balance by decreasing SNS arousal while simultaneously increasing PNS activity.

HRV Biofeedback is Like Weightlifting

Slow-paced breathing used in HRV biofeedback is like weightlifting. Graphic © pixelheadphoto digital skillet/Shutterstock.com.

.jpg)

Just as we only expect athletes to only lift weights during workouts, we don’t expect clients to walk around breathing at 6 bpm constantly. They do not have to continuously breathe at your RF to benefit from improved homeostatic regulation, regulatory capacity, and executive function. Continuous RF breathing would jeopardize homeostasis since breathing rate and volume should adjust to changing physical workloads across the day.

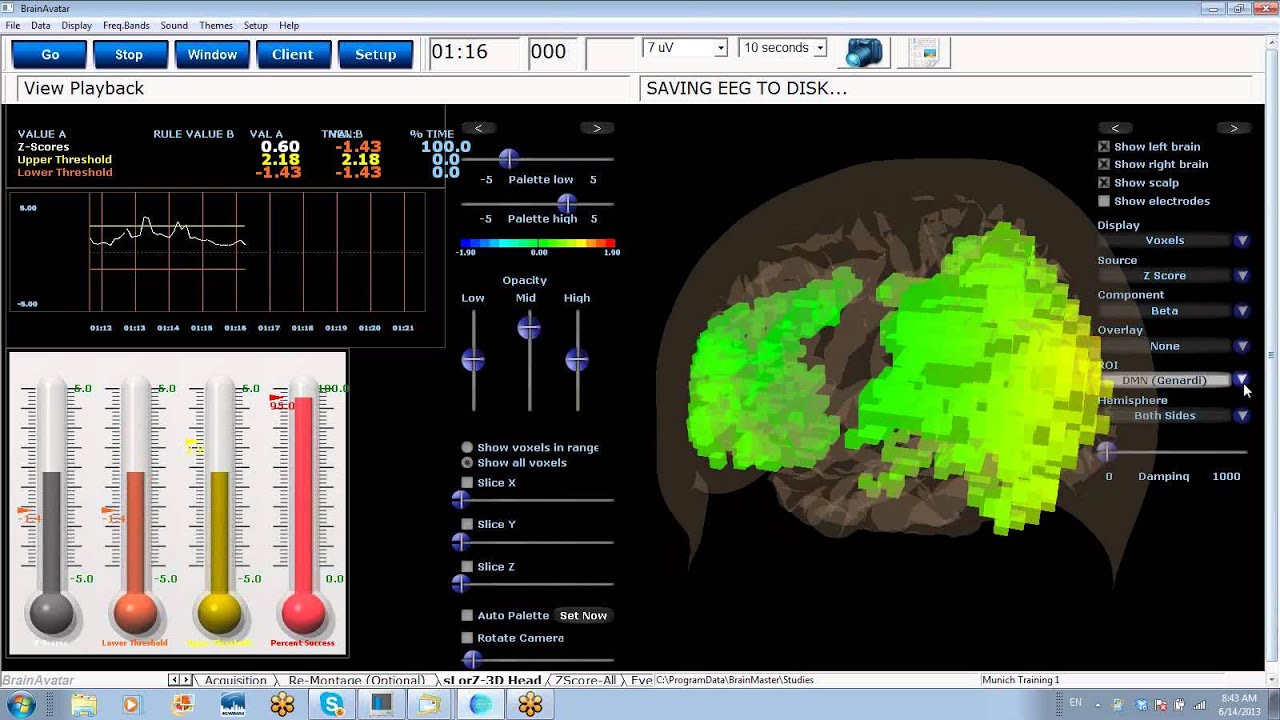

Heart-Brain Interactions

Thayer and Lane (2000) outline a neurovisceral integration model that describes how a central autonomic network (CAN) links the brainstem NST with forebrain structures (including the anterior cingulate, insula, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, and hypothalamus) through feedback and feed-forward loops. They speculate that a breakdown in negative feedback may produce the increased SNS arousal that characterizes anxiety disorders. Thayer et al. (2012, p. 754) contend that regions that include the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex, which evaluate "threat and safety," help regulate HRV through their connections with the NST.

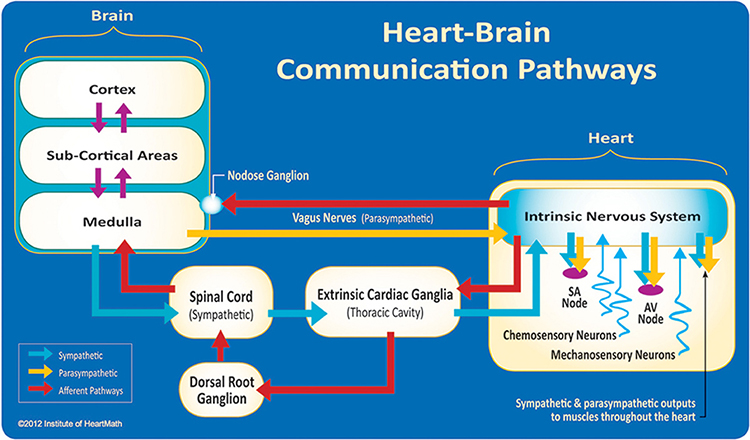

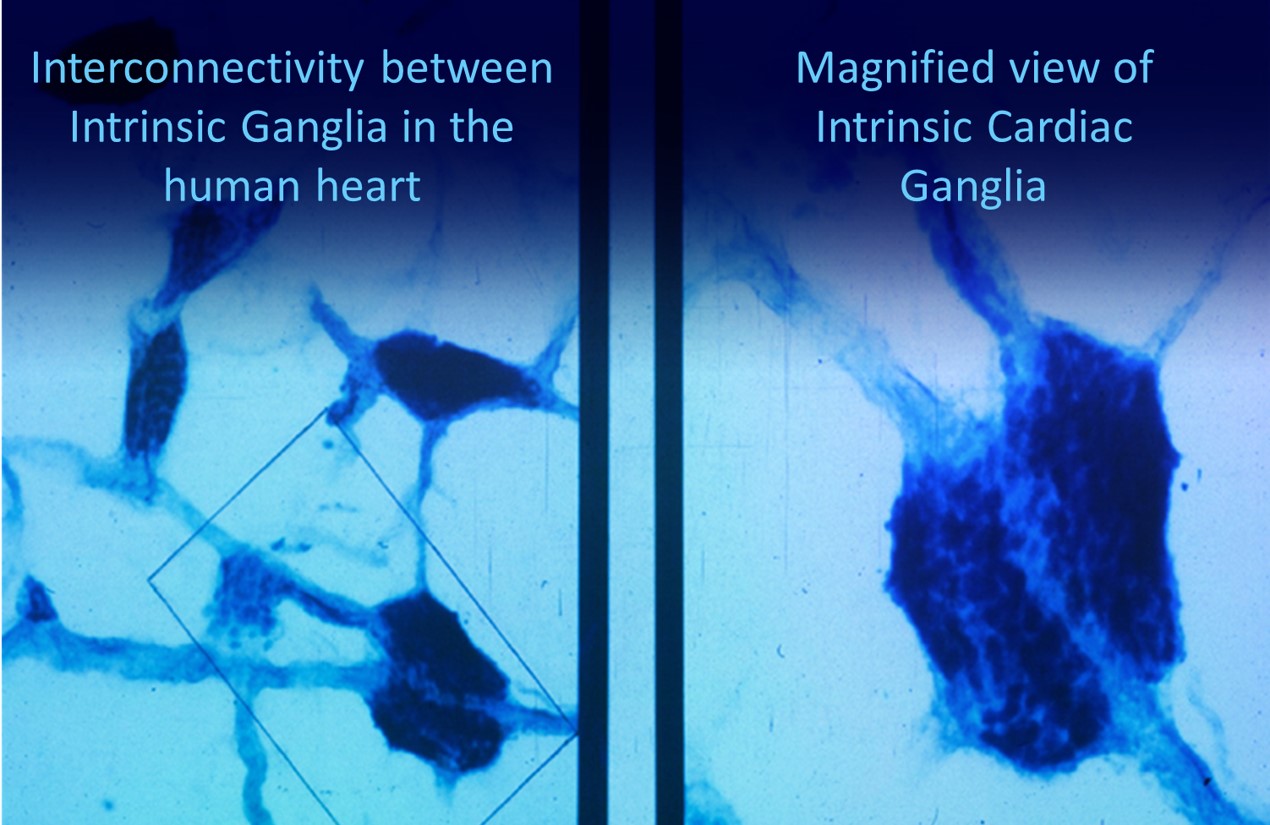

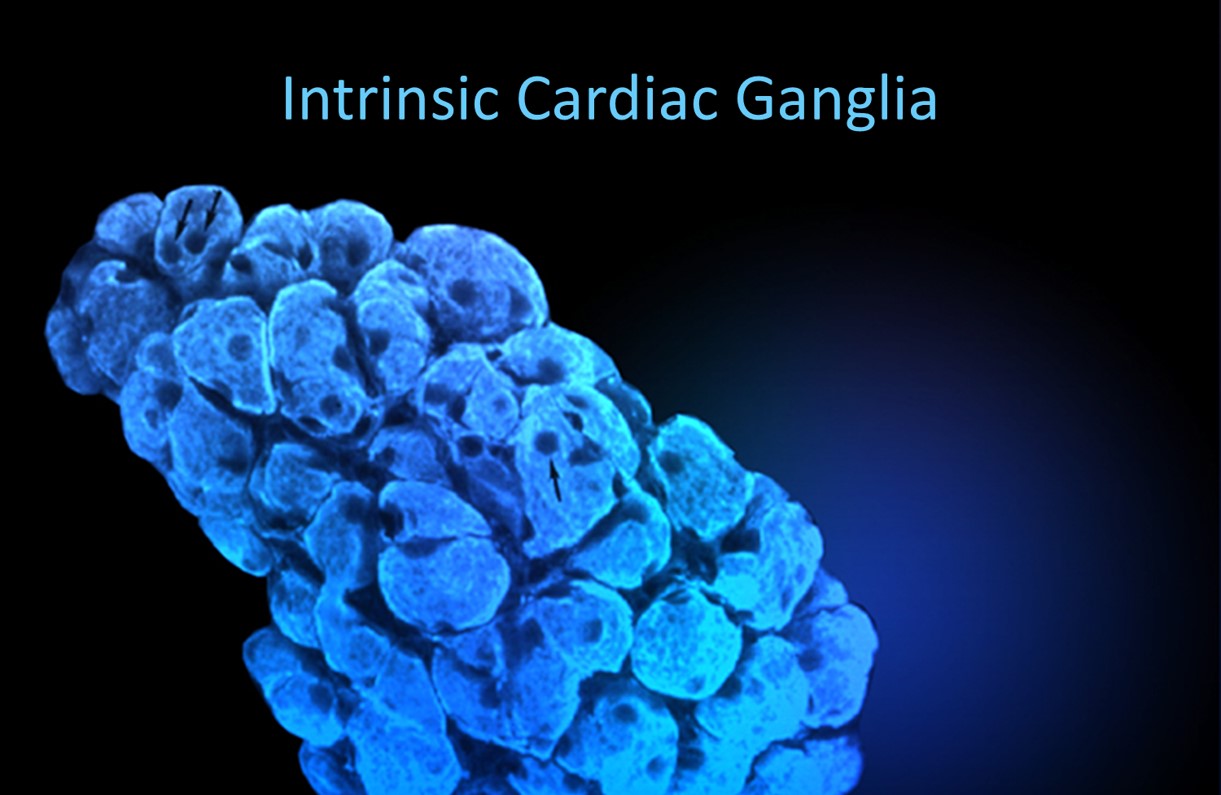

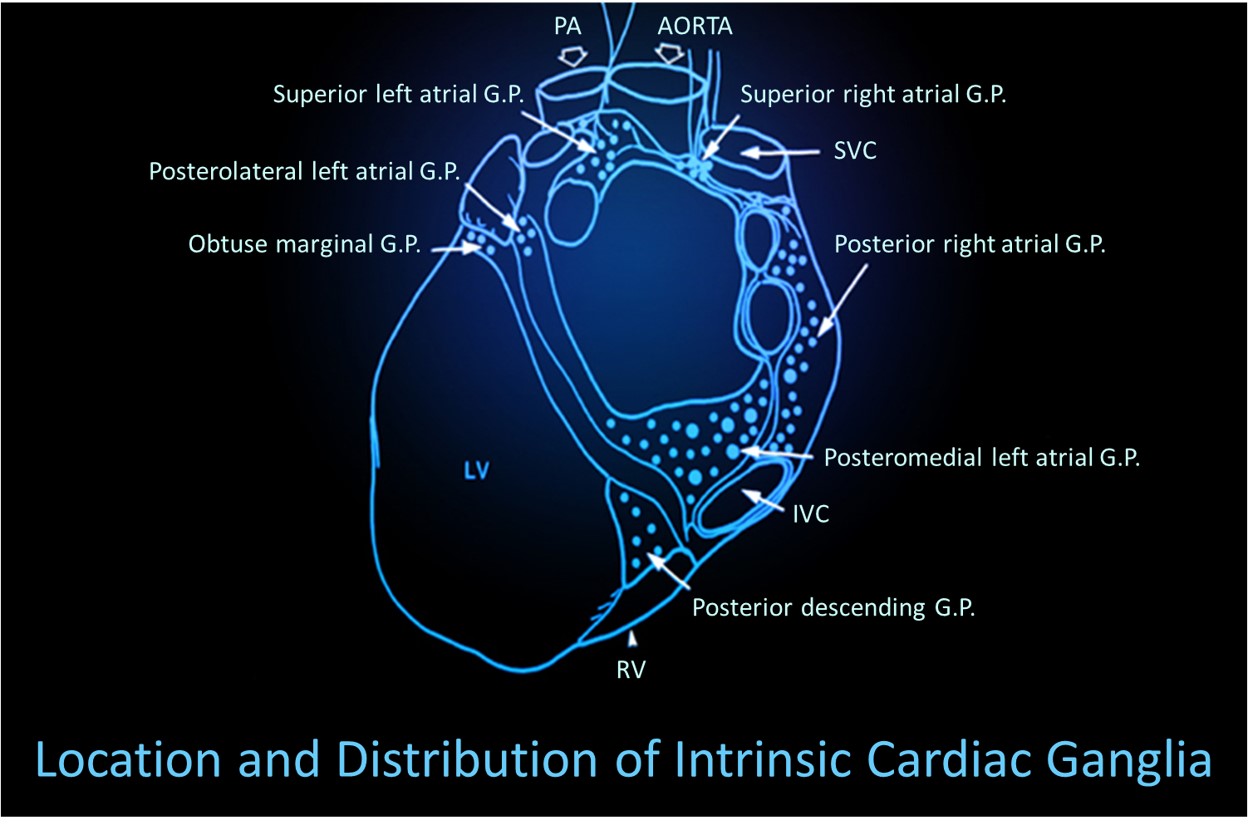

Shaffer, McCraty, and Zerr (2014) propose that interconnected cardiac ganglia create an intrinsic nervous system within the heart that influences the S-A and A-V node pacemakers and forms reciprocal connections with the extrinsic cardiac ganglia found in the chest cavity and the medulla. The sensory, interconnecting, afferent, and motor neurons within the heart can function independently and constitute a "little brain" on the mammalian heart.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Heart-Brain Interactions © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Naeblys/ Shutterstock.com.

The ascending afferent nerves help to regulate the heart and its rhythms physiologically and influence efferent SNS and PNS activity. From 85-90% of vagus nerve fibers are afferents, and more afferents from the heart target the brain than any other major organ.

Afferent signals from the intrinsic cardiac nervous system appear to affect attention, motivation, perceptual sensitivity, and emotional processing (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014). Graphic © 2012 Institute of HeartMath.

MacKinnon, Gevirtz, McCraty, and Brown (2013) reported that HRV influences the amplitude of heartbeat event-related potentials (HERPs). The amplitude of these negative EEG potentials that appear about 200-300 ms after each R-spike indexes cardiac afferent communication with the brain. Both negative and positive emotion conditions reduced HRV and HERP amplitude. In contrast, RF breathing increased HRV above baseline and increased HERP amplitude.

The authors speculated that RF breathing reduces interference with vagal afferent signal transmission from the heart to the cerebral cortex.

The following intrinsic ganglia images © 2012 Dr. Andrew Armour and the Institute of HeartMath.

HRV Myths

Misconception: Variability is bad; stability is good.

Greater variability in instantaneous HR is associated with greater health.

Misconception: The sympathetic nervous system plays a major role in short-term HRV.

Beat-to-beat HR variation is primarily parasympathetic. RSA and the baroreflex are the major PNS sources of brief HRV measurements.

Glossary

0.1 Hz biofeedback: training to concentrate ECG power around 0.1 Hz in the low frequency (LF) band by teaching patients to breathe diaphragmatically at their RF around 6 breaths per minute and to experience positive emotional tone to maximize heart rate variability.

abdominal excursion: the degree of outward and inward stomach movement across the breathing cycle.

baroreceptors: BP sensors located in the aortic arch and internal carotid arteries.

baroreceptor gain: increased baroreceptor sensitivity to BP changes.

baroreceptor reflex (baroreflex): a mechanism that provides negative feedback control of BP. Elevated BP activates the baroreflex to lower BP and low BP suppresses the baroreflex to raise BP.

chemoreceptor: sensors that detect oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood to regulate gas concentration.

chaos: unpredictability due to non-linear dynamics.

cycle length dependence: the phenomenon where faster HRs reduce the time between successive beats and the opportunity for the interbeat intervals (IBIs) to vary, resulting in lower HRV.

epinephrine (E): an adrenal medullary hormone that increases muscle blood flow, converts stored nutrients into glucose for use by skeletal muscles, and initiates cardiac muscle contraction when it binds to β1 receptors.

fractals: infinitely complex geometric patterns that are self-similar across different scales.

frequency-domain measures of HRV: the absolute or relative power of the HRV signal within four frequency bands.

heart rate variability (HRV): the beat-to-beat changes in HR involving changes in the RR intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

high-frequency (HF) band: ECG frequency range from 0.15-0.40 Hz that represents the inhibition and activation of the vagus nerve by breathing (RSA).

homeostasis: a state of dynamic constancy achieved by stabilizing conditions about a setpoint, whose value may change over time.

interbeat interval (IBI): the time interval between the peaks of successive R-spikes (initial upward deflections in the QRS complex). This is also called the NN (normal-to-normal) interval after removing artifacts.

low-frequency (LF) band: an ECG frequency range of 0.04-0.15 Hz that may represent the influence of PNS, SNS, and baroreflex activity (when breathing at the RF).

norepinephrine (NE): an adrenal medullary hormone that initiates cardiac muscle contraction when it binds to β1 receptors.

nucleus ambiguus system: the nucleus dorsal to the inferior olivary nucleus of the upper medulla that gives rise to vagus nerve motor fibers.

resonance frequency: the frequency at which a system, like the cardiovascular system, can be activated or stimulated.

respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA): the respiration-driven heart rhythm that contributes to the high frequency (HF) component of heart rate variability. Inhalation inhibits vagal nerve slowing of the heart (increasing HR), while exhalation restores vagal slowing (decreasing HR).

resting baseline: breathing at typical rates without pacing or feedback.

spectral analysis: the division of heart rate variability into its component rhythms that operate within different frequency bands.

time-domain measures of HRV: indices like SDNN that measure the degree to which the IBIs between successive heartbeats vary.

ultra-low-frequency (ULF) band: an ECG frequency range below 0.003 Hz. Very slow biological processes that include circadian rhythms, core body temperature, metabolism, and the renin-angiotensin system, and possibly the PNS and SNS, generate ULF activity.

vagus nerve: the parasympathetic vagus (X) nerve decreases the rate of spontaneous depolarization in the SA and AV nodes and slows HR. Heart rate increases often reflect reduced vagal inhibition.

vascular tone (VT): the diameter of the blood vessels that regulate BP.

very-low-frequency (VLF): an ECG frequency range of 0.003-.04 Hz that may represent temperature regulation, plasma renin fluctuations, endothelial, physical activity influences, possible intrinsic cardiac nervous system, PNS, and SNS contributions.

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, monitor your HR as you inhale and exhale to observe your own RSA. What is the average difference between your fastest and slowest HRs across several breathing cycles? How has this unit changed how you might explain HRV and its potential benefits to a client.

References

Agelink, M., Boz, C., Ullrich, H., & Andrich, J. (2002). Relationship between major depression and heart rate variability. Clinical consequences and implications for antidepressive treatment. Psychiatry Research, 113(1), 139-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00225-1

Akselrod, S., Gordon, D., Ubel, F. A., Shannon, D. C., Berger, A. C., & Cohen, R. J. (1981). Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: A quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science, 213, 220-222. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6166045

Beckers, F., Verheyden, B., & Aubert, A. E. (2006). Aging and nonlinear heart rate control in a healthy population. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 290, H2560-H2570. https://doi.org/0.1152/ajpheart.00903.2005

Bernardi, L., Valle, F., Coco, M., Calciati, A., & Sleight, P. (1996). Physical activity influences heart rate variability and very-low-frequency components in Holter electrocardiograms. Cardiovascular Research, 32, 234-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-6363(96)00081-8

Bernardi, L., Gabutti, A., Porta, C., & Spicuzza, L. (2001). Slow breathing reduces chemoreflex response to hypoxia and hypercapnia, and increases baroreflex sensitivity. Journal of Hypertension, 19(12), 2221-2229. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200112000-00016

Berntson, G. G., Bigger, J. T., Eckberg, D. L., Grossman, P., Kaufmann, P. G., Malik, M., Nagaraja, H. N., Porges, S. W., Saul, J. P., Stone, P. H., & van der Molen, M. W. (1997). Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology, 34(6), 623-648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x

Berntson, G. G., Quigley, K. S., & Lozano, D. (2007). Cardiovascular psychophysiology. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.). Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bigger, J., Fleiss, J., Rolnitzky, L., & Steinman, R. (1993). The ability of several short-term measures of RR variability to predict mortality after myocardial infarction. Circulation, 88, 927-934. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.88.3.927

Bigger, J., Fleiss, J., Steinman, R., Rolnitzky, L., Kleiger, R., & Rottman, J. (1992). Frequency domain measures of heart period variability and mortality after myocardial infarction. Circulation, 85, 164-171. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.85.1.164

Bigger, J. T., Fleiss, J. L., Steinman, R. C., Rolnitzky, L. M., Schneider, W. J., & Stein, P. K. (1995). RR variability in healthy, middle-aged persons compared with patients with chronic coronary heart disease or recent acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 91(7), 1936-1943. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.91.7.1936

Carney, R. M., Blumenthal, J. A., Stein, P. K., Watkins, L., Catellier, D., Berkman, L. F., Czajkowskim S. M., O'Connor, C., Stone, P. H., & Freedland, K. E. (2001). Depression, heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 104(17), 2024-2028. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc4201.097834

Casolo, G., Balli, E., Taddei, T., Amuhasi, J., & Gori, C. (1989). Decreased spontaneous heart rate variability in congestive heart failure. The American Journal of Cardiology, 64(18), 1162-1167. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(89)90871-0

Cohen, H., & Benjamin, J. (2006). Power spectrum analysis and cardiovascular morbidity in anxiety disorders. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical, 128, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2005.06.007

Dahr, A. K., Lambert, G. W., & Barton, D. A. (2016). Depression and cardiovascular disease: Psychopbiological mechanisms. In M. E. Alvarenga, & D. Byrne (Eds.). Handbook of psychocardiology. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

DeBoer, R. W., Karemaker, J. M., & Strackee, J. (1987). Hemodynamic fluctuations and baroreflex sensitivity in humans: A beat-to-beat model. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 253(22), H680-H689. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.3.h680

Del Pozo, J. M., & Gevirtz, R. N. (2003). Complementary and alternative care for heart disease. Biofeedback, 31(3), 16-17.

Del Pozo, J. M., Gevirtz, R. N., Scher, B., & Guarneria, E. (2004). Biofeedback treatment increases heart rate variability in patients with known coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal, 147(3), G1-G6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2003.08.013

Ewing, D. J., Campbell, I. W., & Clarke, B. F. (1976). Mortality in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Lancet, 1, 601–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90413-X

Gass, J. J., & Glaros, A. G. (2013). Autonomic dysregulation in headache patients. Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 38, 257-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-013-9231-8

Gevirtz, R. (2013). The nerve of that disease: The vagus nerve and cardiac rehabilitation. Biofeedback, 41(1), 32-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.01

Gevirtz, R. N. (2000). Resonant frequency training to restore homeostasis for treatment of psychophysiological disorders. Biofeedback, 27, 7-9.

Gevirtz, R. N. (2003). The promise of HRV biofeedback: Some preliminary results and speculations. Biofeedback, 31(3), 18-19.

Gevirtz, R. N. (2005). Heart rate variability biofeedback in clinical practice. AAPB Fall workshop.

Gevirtz, R. N. (2017). Cardio-respiratory psychophysiology: Gateway to mind-body medicine.

Gevirtz, R. N., & Lehrer, P. (2003). Resonant frequency heart rate biofeedback. In M. S. Schwartz, & F. Andrasik (Eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Gevirtz, R. N., Lehrer, P. M., & Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Cardiorespiratory biofeedback. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Giardino, N. D., Chan, L., & Borson, S. (2004). Combined heart rate variability and pulse oximetry biofeedback for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 29(2), 121-133. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:apbi.0000026638.64386.89

Ginsberg, J. P., Berry, M. E., & Powell, D. A. (2010). Cardiac coherence and posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Alternative Therapies, 16(4), 52-60.

Goldstein, D. S., Bentho, O., Park, M. Y., & Sharabi, Y. (2011). Low frequency power of heart rate variability is not a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone but may be a measure of modulation of cardiac autonomic outflows by baroreflexes. Exp Physiol, 96(12), 1255-1261. PMID: 20653296

Herbs, D., Gevirtz, R. N., & Jacobs, D. (1994). The effect of heart rate pattern biofeedback for the treatment of essential hypertension [Abstract]. Biofeedback and Self-regulation, 19(3), 281.

Imahori, Y., Vetrano, D. L., Xia, X., Grande, G., Ljungman, P., Fratiglioni, L., & Qui, C. (2021). Association of resting heart rate with cognitive decline and dementia in older adults: A population-based cohort study. Alzheimer's & Dementia. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12495

Karemaker, J. M. (2009). Counterpoint: Respiratory sinus arrhythmia is due to the baroreflex mechanism. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(5), 1742–1743. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.91107.2008a

Kazuma, N., Otsuka, K., Matsuoka, I., & Murata, M. (1997). Heart rate variability during 24 hours in asthmatic children. Chronobiol Int, 14, 597–606. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420529709001450

Kleiger, R. E., Miller, J. P., Bigger, J. T., & Moss, A. J. (1987). Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. American Journal of Cardiology, 59, 256-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(87)90795-8

Lehrer, P. M. (2007). Biofeedback training to increase heart rate variability. In P. M. Lehrer, R. M. Woolfolk, & W. E. Sime (Eds.). Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Lehrer, P. M. (2012). Personal communication.

Lehrer, P. M. (2013). How does heart rate variability biofeedback work? Resonance, the baroreflex, and other mechanisms. Biofeedback, 41(1), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.02

Lehrer, P. M., & Eddie, D. (2013). Dynamic processes in regulation and some implications for biofeedback and biobehavioral interventions. Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 38, 143-155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-013-9217-6

Lehrer, P. M., & Gevirtz, R. (2021). BCIA HRV Biofeedback didactic workshop. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Lehrer, P., Karavidas, M. K., Lu, S. E., Coyle, S. M., Oikawa, L. O., Macor, M., Calvano, S. E., & Lowry, S. F. (2010). Voluntarily produced increases in heart rate variability modulate autonomic effects of endotoxin induced systemic inflammation: An exploratory study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 35(4), 303-315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-010-9139-5

Lehrer, P. M., Smetankin, A., & Potapova, T. (2000). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback therapy for asthma: A report of 20 unmedicated pediatric cases using the Smetankin method. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25, 193-200. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009506909815

Lehrer, P. M., & Vaschillo, E. (2008). The future of heart rate variability biofeedback. Biofeedback, 36(1), 11-14.

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lu, S. E., Eckberg, D. L., Edelberg, R., Shih, W. J., Lin, Y., Kuusela, T. A., Tahvanainen, K. U. O., & Hamer, R. M. (2003). Heart rate variability biofeedback increases baroreflex gain and peak expiratory flow. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 796-805. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000089200.81962.19

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E. V., & Vaschillo, B. (2004). Heartbeat synchronizes with respiratory rhythm only under specific circumstances. Chest, 126(4), 1385-1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-3692(15)31329-5

Lehrer, P., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lu, S-E, Scardella, A., Siddique, M, & Habib, R. (2004). Biofeedback treatment for asthma. Chest, 126, 352-361. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.126.2.352

Lehrer, P., Vaschillo, B., Zucker, T., Graves, J., Katsamanis, M., Aviles, M., & Wamboldt, F. (2013). Protocol for heart rate variability biofeedback training. Biofeedback, 41(3), 98-109.

MacLean, B. (2004). The heart and the breath of love. Biofeedback, 32(4), 21-25.

Maver, J., Strucl, M., & Accetto, R. (2004). Autonomic nervous system activity in normotensive subjects with a family history of hypertension. Clinical Autonomic Research: Official Journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society, 14(6), 369-375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-004-0185-z

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tiller, W. A. (1995). The effects of emotions on short term power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. American Journal of Cardiology, 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80309-9

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tomasino, D., & Bradley, R. T. (2006). The coherent heart. Boulder Creek, CA: Institute of HeartMath.

McCraty, R., Atkinson M, Tomasino, D., & Bradley, R. T. (2009). The coherent heart: Heart-brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. Integral Review, 5(2), 10-115.

McCraty, R. & Shaffer, F. (2015). Heart rate variability: New perspectives on physiological mechanisms, assessment of self-regulatory capacity, and health risk. Glob Adv Health Med, 4(1). 46-61. https://doi.org/10.7453/gahmj.2014.073

Moravec, C. S., & McKee, M. G. (2013). Biofeedback in heart failure: Psychophysiologic remodeling of the failing heart. Biofeedback, 41(1), 7-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.04

Moss, D. (2004). Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback. Psychophysiology Today, 1, 4-11.

Nolan, J., Flapan, A. D., Capewell, S., MacDonald, T. M., Neilson, J. M., & Ewing, D. J. (1992). Decreased cardiac parasympathetic activity in chronic heart failure and its relation to left ventricular function. Br Heart J, 67(6), 482-485. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.67.6.482

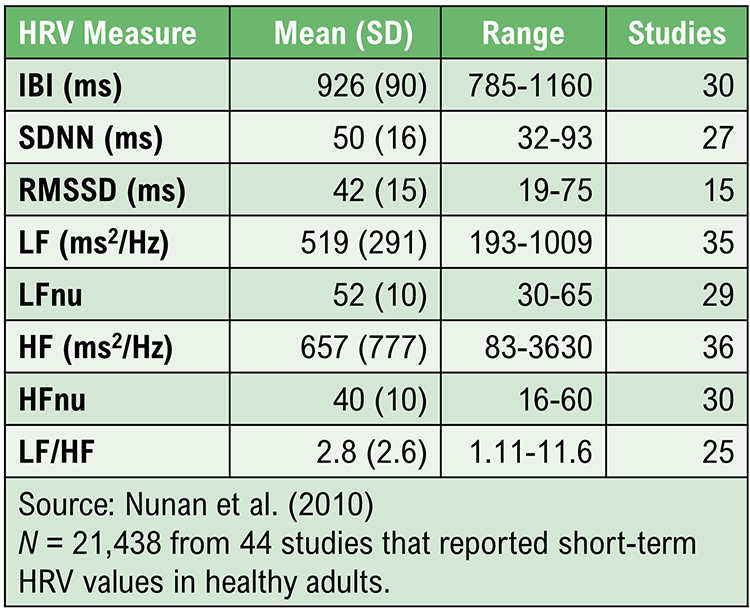

Nunan, D., Sandercock, G. R. H., & Brodie, D. A. (2010). A quantitative systematic review of normal values for short-term heart rate variability in healthy adults. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 33(11), 1407-1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02841.x

Ogletree-Hughes, M. L., Stull, L. B., Sweet, W. E., Smedira, N. G., McCarthy, P. M., & Moravec, C. S. (2001). Mechanical unloading restores beta-adrenergic responsiveness and reverses receptor down-regulation in the failing human heart. Circulation, 104, 881-886. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc3301.094911

Olshansky, B., Sabbah, H. N., Hauptman, P. J., & Colucci, W. S. (2008). Parasympathetic nervous system and heart failure: Pathophysiology and potential implications for therapy. Circulation, 118, 863-871. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.107.760405

Opthof, T. (2000). The normal range and determinants of the intrinsic heart rate in man. Cardiovascular Research, 45, 177-184. PMID: 10728332

Papillo, J. F., & Shapiro, D. (1990). The cardiovascular system. In J. T. Cacioppo & L. G. Tassinary (Eds.) Principles of psychophysiology: Physical, social, and inferential elements (pp. 456 - 512). Cambridge University Press.

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Lin, I., Tylova, H., & Moss, D. (2007). Is there more to blood volume pulse than heart rate variability, respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and cardio-respiratory synchrony? Biofeedback, 35(2), 54-61.

Poole, L., Dickens, C., & Steptoe, A. (2011). The puzzle of depression and acute coronary syndrome: Reviewing the role of acute inflammation. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 71(2), 61-68.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. W. Norton & Company.

Ridker, P. M., Rifai, N., Stampfer, M. J., & Hennekens, C. H. (2000). Plasma concentration interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation, 101(15), 1767-1772. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.15.1767

Roach, D., Wilson, W., Ritchie, D., & Sheldon, R. (2004). Dissection of long-range heart rate variability: Controlled induction of prognostic measures by activity in the laboratory. J Am Coll Cardiol, 43(12), 2271-2277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.050

Schmidt, J. E., Carlson, C. R. (2009). A controlled comparison of emotional reactivity and physiological response in masticatory muscle pain patients. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 23, 230-242. PMID: 19639103

Schwartz, S. (2015). Viva vagus: Wandering nerve could lead to range of therapies. Science News, 188(11), 18.

Shaffer, F., & Combatalade, D. C. (2013). Don't add or miss a beat: A guide to cleaner heart rate variability recordings. Biofeedback, 41(3), 121-130.

Shaffer, F., McCraty, R., & Zerr, C. L. (2014). A healthy heart is not a metronome: An integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01040

Shaffer, F., Meehan, Z. M., & Zerr, C. L. (2020). A critical review of ultra-short-term heart rate variability norms research. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

Shaffer, F., & Moss, D. (2006). Biofeedback. In Y. Chun-Su, E. J. Bieber, & B. Bauer (Eds.). Textbook of complementary and alternative medicine (2nd ed.). Informa Healthcare.

Stauss, H. M. (2003). Heart rate variability. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 285, R927-R931. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00452.2003

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (1996). Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation, 93, 1043-1065. PMID: 8598068

Taylor, J. A., Carr, D. L., Myers, C. W., & Eckberg, D. L. (1998). Mechanisms underlying very-low-frequency RR-interval oscillations in humans. Circulation, 98, 547-555. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.98.6.547

Taylor, S. E. (2006). Tend and befriend: Biological bases of affiliation under stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 273-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00451.x

Thayer, J. F., Ahs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J., & Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36, 747-756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009

Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61, 201-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00338-4

Thayer, J. F., Yamamoto, S. S., & Brosschot, J. F. (2010). The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int J Cardiol, 141(2), 122-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.543

Umetani, K., Singer, D. H., McCraty, R., & Atkinson, M. (1998). Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: Relations to age and gender over nine decades. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 31(2), 593-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00554-8

Vaillancourt, D. E., & Newell, K. M. (2002). Changing complexity in human behavior and physiology through aging and disease. Neurobiology of Aging, 23, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00247-0

Vaschillo, E., Lehrer, P., Rishe, N., & Konstantinov, M. (2002). Heart rate variability biofeedback as a method for assessing baroreflex function: A preliminary study of resonance in the cardiovascular system. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014587304314

Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., & Lehrer, P. (2004). Heartbeat synchronizes with respiratory rhythm only under specific circumstances. Chest, 126, 1385-1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-3692(15)31329-5

Vaschillo, E. G., Vaschillo, B., Pandina, R. J., & Bates, M. E. (2011). Resonances in the cardiovascular system caused by rhythmical muscle tension. Psychophysiology, 48, 927-936. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01156.x

Wolf, M. M., Varigos, G. A., Hunt, D., & Sloman, J. G. (1978). Sinus arrhythmia in acute myocardial infarction. Med J Australia, 2, 52-53. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1978.tb131339.x

Yasuma, F., & Hayano, J. (2004). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Why does the heartbeat synchronize with respiratory rhythm? Chest, 125(2), 683-690. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.2.683

Zhang, D., Shen, X., & Qi, X. (2016). Resting heart rate and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population: A meta-analysis. CMAJ, 188(3), E53-63. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150535

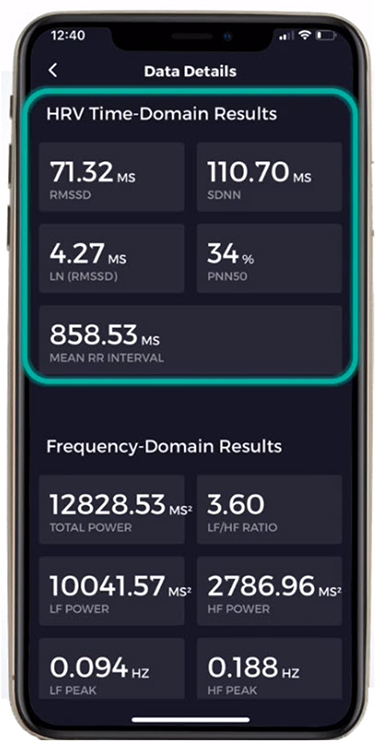

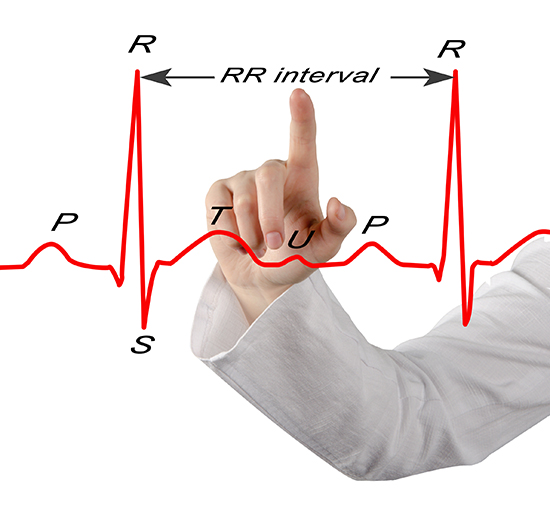

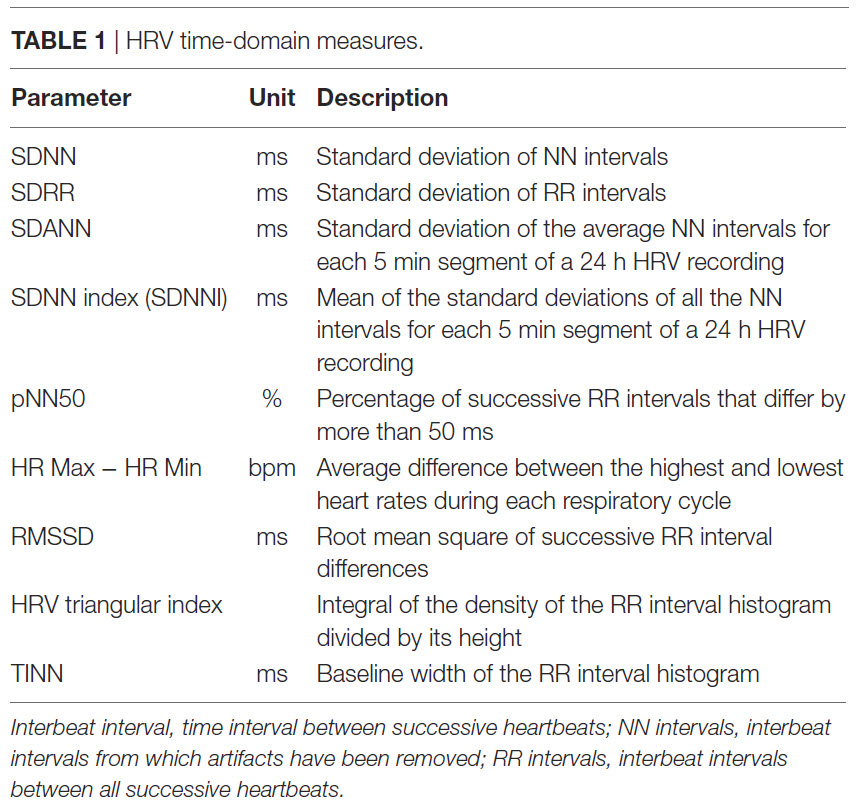

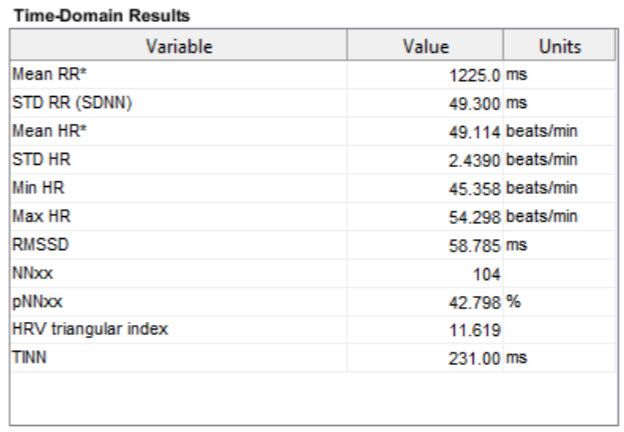

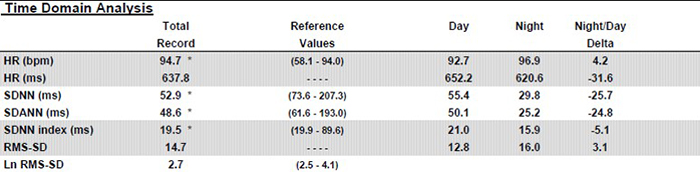

B. HRV TIME-DOMAIN MEASUREMENTS

Normative heart rate variability (HRV) values only apply when clients breathe at average rates (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017).

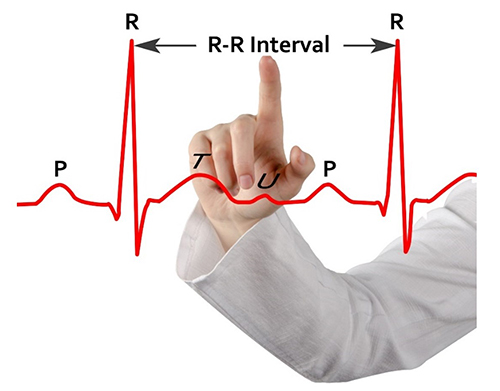

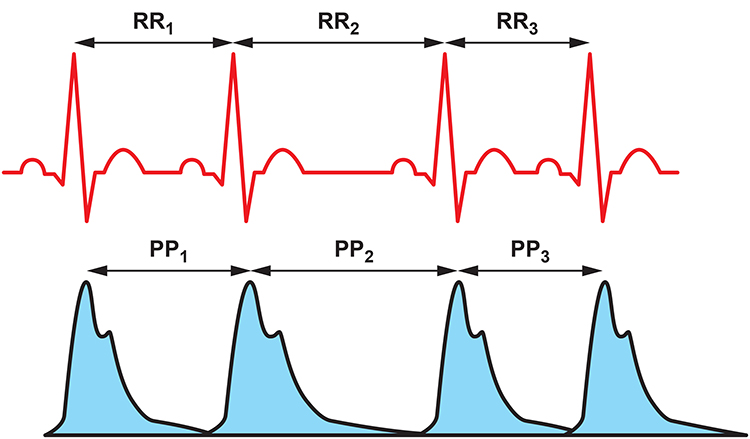

HRV time-domain indices quantify the amount of variability in measurements of the interbeat interval (IBI), which is the period between successive heartbeats. An IBI is called an R-R interval because it is the time between adjacent R-spikes. Graphic © arka38/Shutterstock.com

We measure the time intervals between successive heartbeats in milliseconds (ms). The software starts counting after detecting the first beat and calculates the first IBI in milliseconds after detecting the second beat. This process is repeated until the end of the epoch or data collection period. Graphic courtesy of Dick Gevirtz.

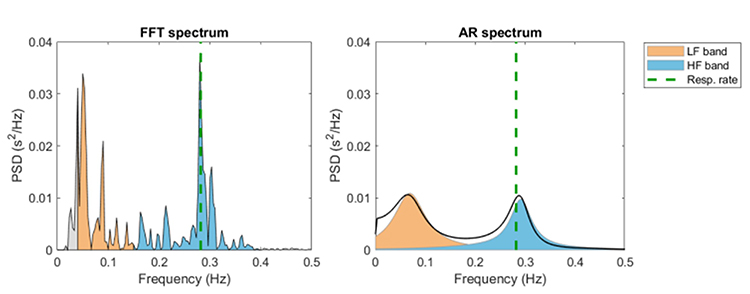

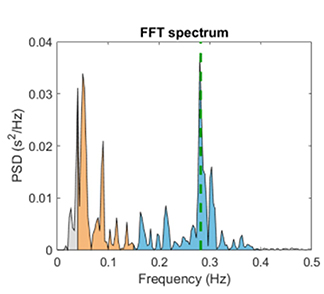

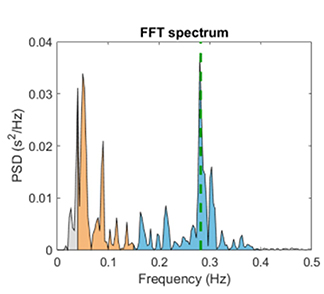

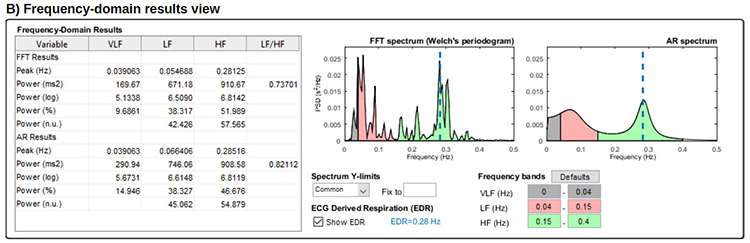

In contrast, HRV frequency-domain measurements calculate the absolute or relative amount of signal power in the ULF, VLF, LF, and HF bands. The graphic below shows two methods of measuring the spectral distribution of HRV power (FFT and Autoregression). The graphic is courtesy of Tarvainen and Niskanen (2020).

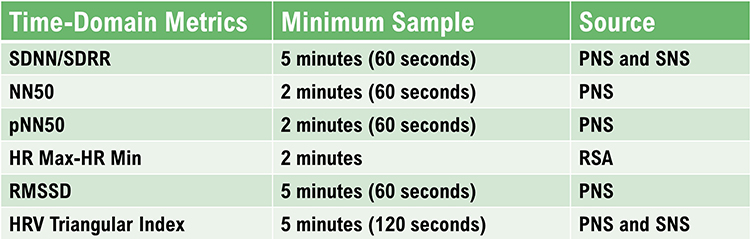

This section covers the SDNN, SDRR, SDANN, pNN50, NN50, HR Max - HR Min, RMSSD, and HRV triangular index.

SDNN

The SDNN is the standard deviation of the interbeat interval of normal sinus beats measured in milliseconds (ms). "Normal" means that abnormal beats, like ectopic beats, have been removed. The related SDSD, the standard deviation of successive RR interval differences, only represents short-term variability.

SDNN is calculated using data that are free of artifacts and abnormal heartbeats.

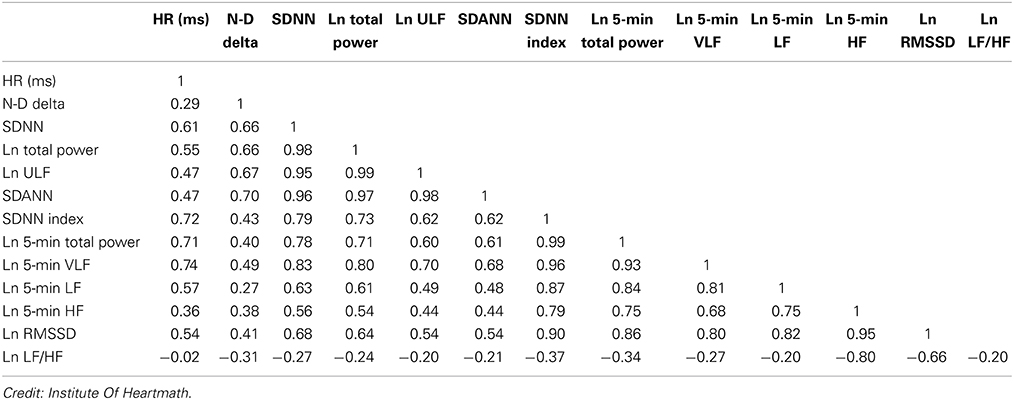

Both SNS and PNS activity contribute to SDNN, and it is highly correlated with ULF, VLF, LF band power, and total power (Umetani et al., 1998). This relationship depends on the measurement conditions. When these bands have greater power than the HF band, they contribute more to SDNN.In short-term (≤ 5 minutes) resting recordings, the primary source of the variation is parasympathetically-mediated RSA, especially with slow-paced breathing protocols (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

In 24-hour recordings, LF band power contributes significantly to SDNN (Kusela, 2013). The following table shows the correlations between time- and frequency-domain measures in 24-hour recordings and is provided courtesy of the Institute of HeartMath (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

Why 24 Hour Recording is More Accurate

The SDNN is more accurate when calculated over 24 hours than during the shorter periods monitored during biofeedback sessions. More extended recording periods provide data about cardiac reactions to a greater range of environmental stimulation. In addition to cardiorespiratory regulation, extended measurement periods can index the heart's response to changing workloads, anticipatory central nervous activity involving classical conditioning, and circadian processes, including sleep-wake cycles (Lehrer, 2012). Twenty-four-hour recordings reveal the SNS contribution to HRV (Grant et al., 2011).While the conventional brief recording standard is 5 minutes, researchers have proposed ultra-short-term (UST) recording periods from 60 (Salahuddin et al., 2007; Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020) to 240 seconds (Baek et al., 2015).

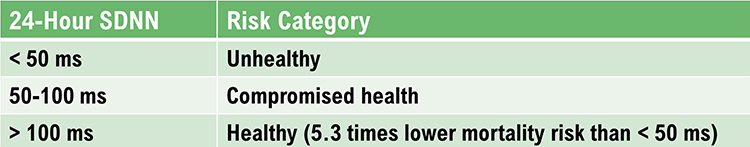

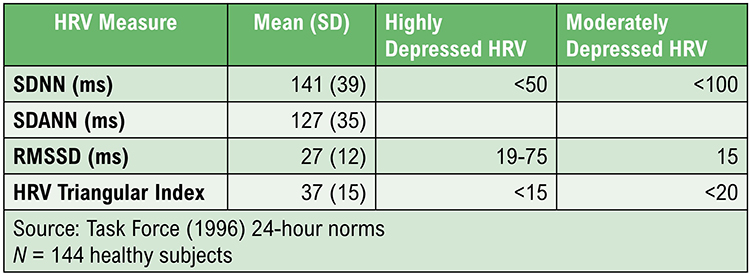

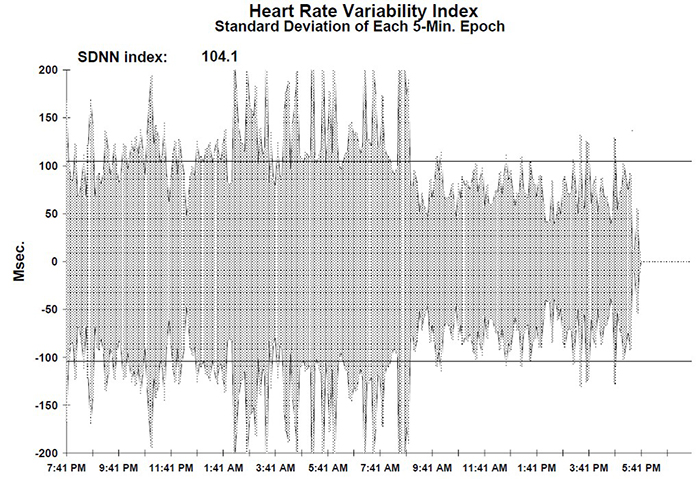

24-Hour SDNN Predicts Mortality

The SDNN is the "gold standard" for medical stratification of cardiac risk when recorded 24 hours (Task Force, 1996). SDNN values predict both morbidity and mortality. Based on 24-hour monitoring, patients with SDNN values below 50 milliseconds are classified as unhealthy, 50-100 milliseconds have compromised health, and above 100 milliseconds are healthy.

Heart attack survivors, whose 24-hour measurements placed them in a higher category, had a greater probability of living during a 31-month mean follow-up period. For example, patients with SDNN values over 100 milliseconds had 5.3 times lower mortality risk at follow-up than those under 50 milliseconds (Kleiger et al., 1987). Does this mean that training patients to increase SDNN to a higher category could reduce their mortality risk?

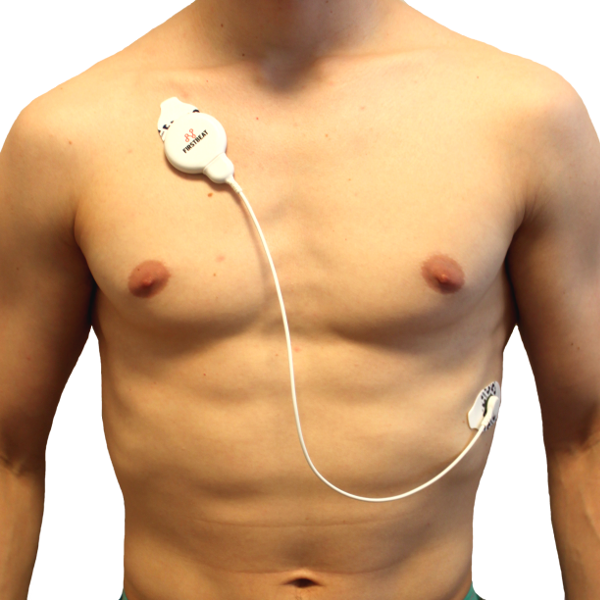

An ECG sensor designed for ambulatory 24-hour monitoring is shown below.

|

|

SDRR

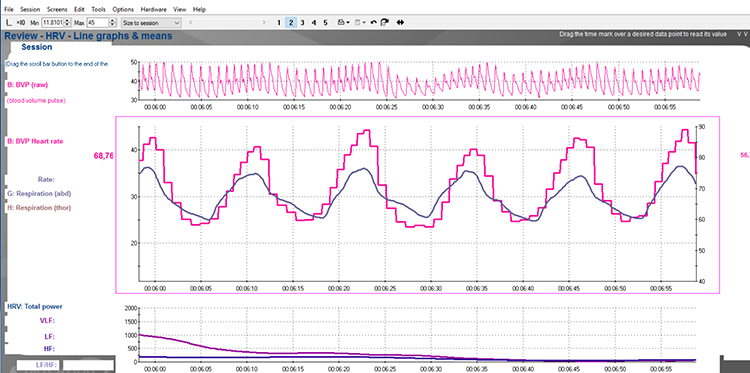

The SDRR is the standard deviation of the interbeat interval for all sinus beats (including abnormal or false beats) measured in ms. As with the SDNN, the SDRR calculates how these intervals vary over time. The SDRR is also more accurate when calculated over 24 hours. Abnormal beats may reflect cardiac dysfunction or noise that masquerades as HRV. Below is a heart rate variability display. The roller coaster accelerates as SDRR increases.

SDANN

The SDANN is the standard deviation of the average NN intervals for each of the 5-minute segments during a 24-hour recording. NN intervals stands for normal-to-normal intervals. These are "clean" IBIs calculated after artifacting the data. The SDANN estimates heart rate (HR) changes produced by cycles longer than 5 minutes. Like the SDNN, it is measured and reported in milliseconds. This index is correlated with the SDNN and is generally considered redundant (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014). Minimum HR is more strongly associated with Ln SDANN than Ln RMSSD. Ln means the natural logarithm. Maximum heart rate is weakly and inconsistently correlated with these time-domain measures (Burr et al., 2006).

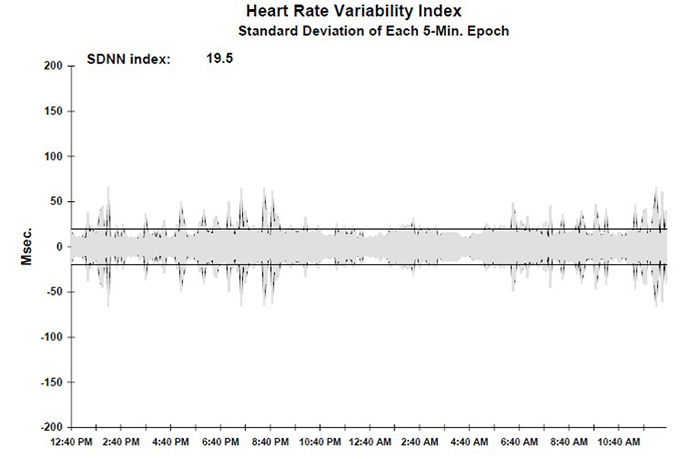

SDNN Index (SDNNI)

The SDNN Index (SDNNI) is the mean of the standard deviations of all the NN intervals for each 5-minute segment of a 24-hour HRV recording. Therefore, this measurement only estimates variability due to the factors affecting HRV within 5 minutes. It is calculated by dividing the 24-hour record into 288 5-minute segments and then calculating the standard deviation of all NN intervals within each segment. The SDNNI is the average of these 288 values.

The SDNNI is believed to measure autonomic influence on HRV primarily. The SDNNI tends to correlate with VLF power over over 24 hours (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

NN50

The NN50 measures the number of adjacent NN intervals that differ by more than 50 milliseconds. At least a 2-minute sample is required.

pNN50

The pNN50 is the percentage of adjacent NN intervals that differ from each other by more than 50 milliseconds. While the conventional minimum recording is 5 minutes, researchers have proposed UST periods of 10 seconds (Salahuddin et al., 2007), 30 seconds (Baek et al., 2015), and 60 seconds (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

The pNN50 is closely correlated with PNS activity (Umetani et al., 1998). It is correlated with the RMSSD and HF power. However, the RMSSD typically provides a better assessment of RSA (especially in older subjects), and most researchers prefer it to the pNN50 (Otzenberger et al., 1998). The pNN50 may be a more reliable index than short-term SDNN measurements for the brief samples used in biofeedback.

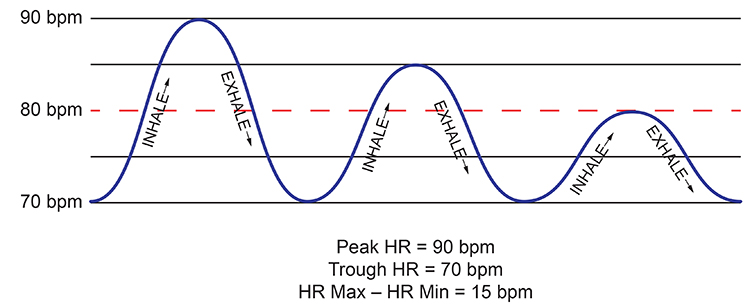

HR Max-HR Min

HR Max – HR Min is the average difference between the highest and lowest heart rates during each respiratory cycle. At least a 2-minute sample is required to calculate HR Max – HR Min. Physically active individuals show wider peak-trough differences than those who are sedentary.

HR Max-HR Min is Affected by Breathing Rate and Measures RSA

This index is susceptible to the effects of respiration rate, independent of vagus nerve traffic. Instead of directly indexing vagal tone, it reflects RSA. HR Max-HR Min depends on age and fitness. Since longer exhalations allow greater acetylcholine metabolism, slower respiration rates can produce higher RSA amplitudes that are not mediated by changes in vagal firing (Lehrer, 2012).Booiman (2017) reported values in the 30- and 40-bpm range for Dutch clients in their teens and twenties during slow-paced breathing. For example, the screen capture below is from a 16-year-old female client, 2 weeks post-concussion, who achieved a HR Max-HR Min value of 30 bpm while breathing at 5.5 breaths per minute. Graphic courtesy of Annette Booiman.

HR Max-HR Min can reach 50 beats per minute for elite athletes. This measure is used for HRV assessment in paced breathing protocols and is highly correlated with the SDNN and RMSSD (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

RMSSD

The RMSSD is the root mean square of successive differences between normal heartbeats. This value is obtained by first calculating each subsequent time difference between adjacent interbeat intervals in milliseconds. Then, each of these values is squared, and the result is averaged before the square root of the total is obtained.

The RMSSD reflects rapid beat-to-beat variance in HR and better estimates vagal activity than SDNN (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014). The RMSSD is conceptualized as vagally-mediated HRV (vmHRV; Jarczock et al., 2021). The RMSSD is the best overall measure of short-term HRV because it is less affected by outliers and artifacts than SDNN (Gevirtz, 2020). A novel ratio of short-term RMSSD and C-reactive protein predicted survival in cancer patients and the general population (Jarczock et al., 2021). At least a 5-minute sample is required. Researchers have proposed UST periods of 10 seconds (Salahuddin et al., 2007), 30 seconds (Baek et al., 2015), and 60 seconds (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

The RMSSD is identical to the nonlinear metric SD1, reflecting short-term HRV (Ciccone et al., 2017). While the RMSSD is correlated with HF power (Kleiger et al., 2005), the influence of respiration rate on this index is uncertain (Schipke et al., 1999; Pentillä et al., 2001). The RMSSD is less affected by respiration than is RSA across several tasks (Hill & Siebenbrock, 20009). The RMSSD is more influenced by the PNS than SDNN (Gevirtz, 2017).

Lower RMSSD values are correlated with higher scores on a risk inventory of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (DeGiorgio et al., 2010).

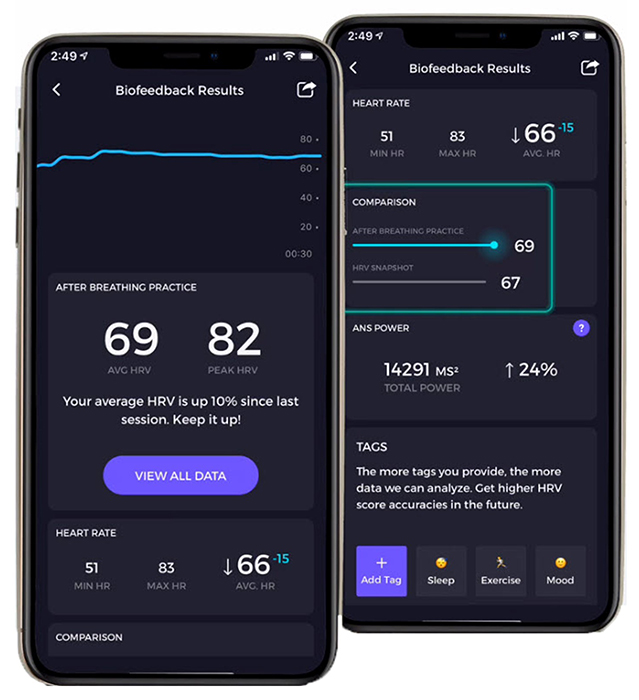

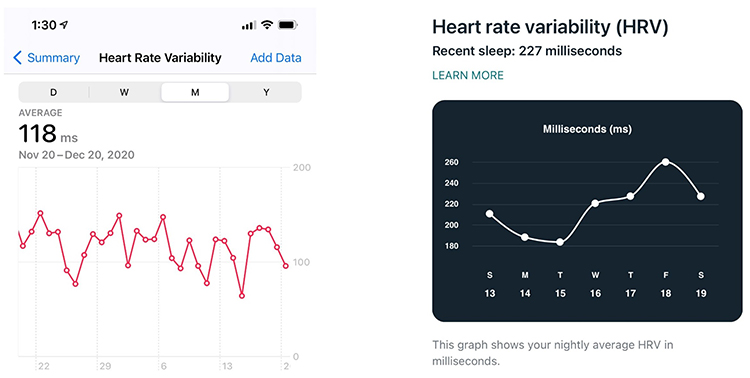

Many HRV apps (Apple Health, Elite HRV, Fitbit) use RMSSD or Ln RMSSD to measure HRV. Ln means the natural logarithm.

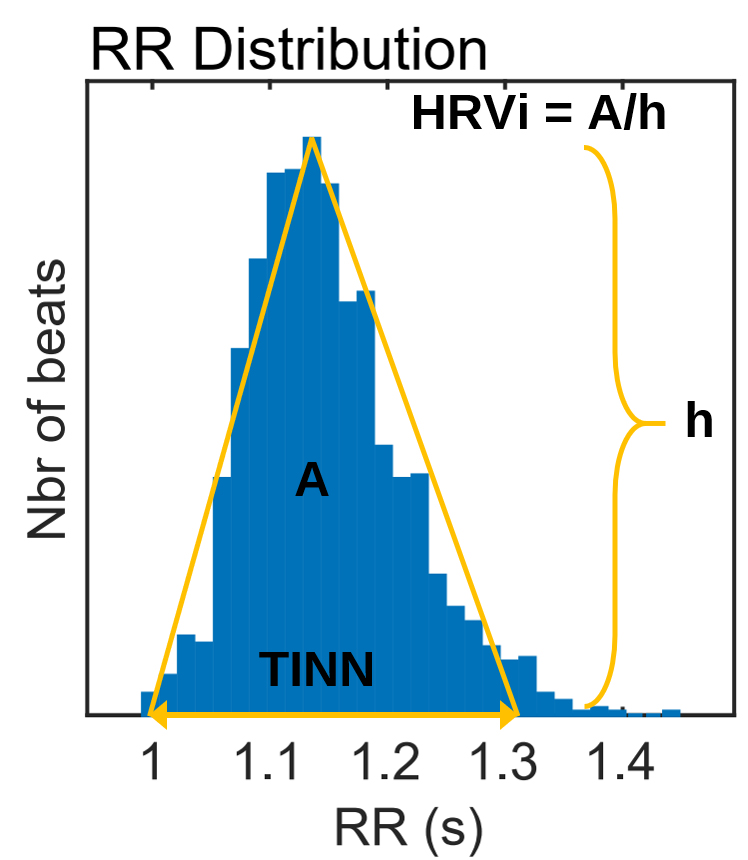

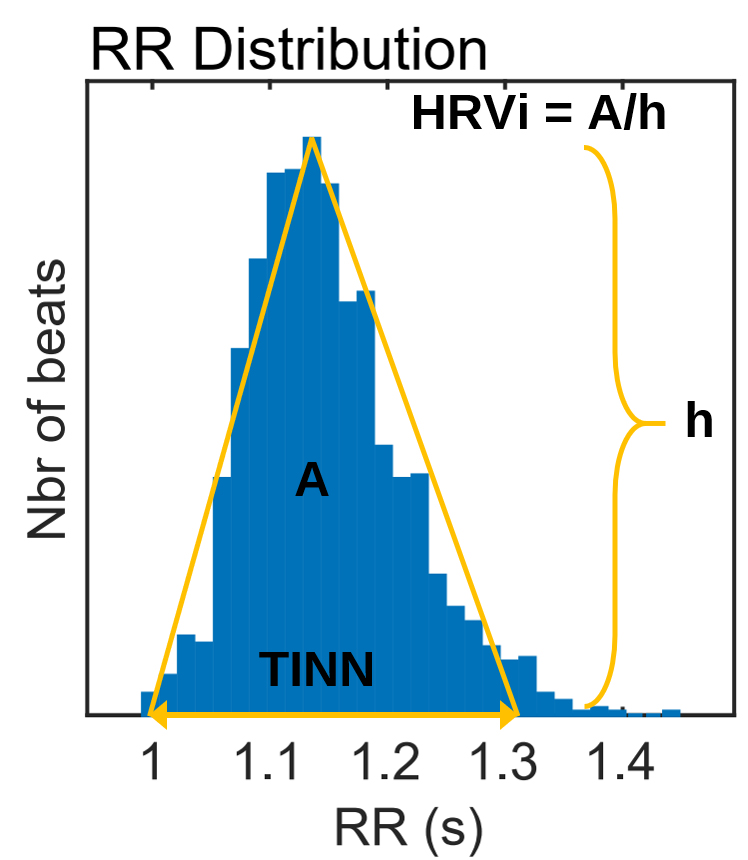

HRV Triangular Index

The HRV triangular index (HTI) is a geometric measure based on 24-hour recordings, which calculates the integral of the RR interval histogram's density divided by its height (Task Force, 1996). Graphic retrieved from vippng.com.

Both the PNS and SNS contribute to the HRV triangular index (Billman et al., 1982; Schwartz et al., 1988). A 5-minute epoch may be sufficient to represent this metric (Jovic & Bogunovic, 2011). A 120-second UST period estimated this metric (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

HTI and RMSSD can jointly distinguish between normal heart rhythms and arrhythmias (Jovic & Bogunovic, 2011). The HTI independently predicts mortality in patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (Hämmerle et al., 2020). When HTI ≤ 20.42 and RMSSD ≤ 0.068, the heart rhythm is normal. When HTI > 20.42, the rhythm is arrhythmic (Jovic & Bogunovic, 2011).

Summary Tables

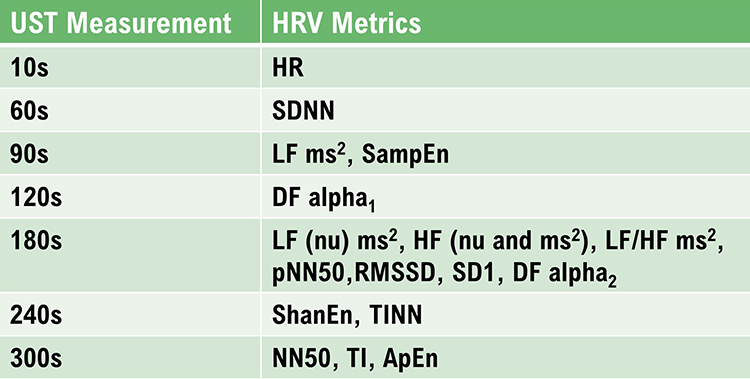

Table 2 shows the minimum conventional and UST recording periods (Shaffer, Meehan, and Zerr, 2020).

Table 3 displays Kubios time-domain calculations after artifact correction.

The Triangular Interpolation of the NN Interval Histogram

The Triangular Interpolation of the NN Interval Histogram (TINN) is the baseline width of a histogram displaying NN intervals. To unpack this definition, visualize a histogram that plots the frequency of NN intervals. The X-axis represents interbeat interval length in milliseconds, and the Y-axis represents the number of intervals of identical length (Yilmaz et al., 2018). At least a 5-minute sample is required (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). Graphic retrieved from vippng.com.

HRV Myths

Misconception: Short-term and 24-hour measurements are interchangeable.

You cannot interpret short-term metrics using 24-hour norms because they were obtained under different conditions. Briefer recording periods generally underestimate HRV.

Misconception: We can interpret 5-minute slow-paced breathing measurements using 5-minute resting norms.

A resting condition means that participants breathe at typical rates (e.g., 12-14 bpm). You cannot compare its values with resting norms since slow-paced breathing is less than half that rate and increases RSA.

Misconception: We can use UST and short-term measurements interchangeably.

UST measurements are more vulnerable to corruption by artifact because they are based on fewer data points. Currently, there is no consensus on acceptable UST-measurement length. "UST measurements are proxies of proxies. They seek to replace short-term values, which, in turn, attempt to estimate reference standard long-term metrics" (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

A clinician calculates an SDNN value of 60 milliseconds from a 15-minute resting baseline and is concerned that his client may have an elevated heart attack risk. What has he overlooked?

He has mistakenly applied cutoffs based on 24-hour recordings to brief recordings. Twenty-four-hour and brief recording values are not interchangeable since short monitoring periods exclude long-term sources of HRV like circadian rhythms.

Glossary

heart rate: the number of heartbeats per minute, also called stroke rate.

heart rate variability (HRV): the beat-to-beat changes in HR involving changes in the RR intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

HR Max – HR Min: an HRV index that calculates the average difference between the highest and lowest HRs during each respiratory cycle.

HRV triangular index (HTI): a geometric measure based on 24-hour recordings, which calculates the integral of the RR interval histogram's density divided by its height.

interbeat interval (IBI): the time interval between the peaks of successive R-spikes (initial upward deflections in the QRS complex).

NN50: the number of adjacent NN intervals that differ from each other by more than 50 milliseconds.

NN interval: the normal-to-normal interval is an IBI after artifacts have been removed.

pNN50: the percentage of adjacent NN intervals that differ from each other by more than 50 milliseconds.

RMSSD: the square root of the mean squared difference of adjacent NN intervals.

SDANN: the standard deviation of the average NN intervals (mean heart rate) for each of the 5-minute segments during a 24-hour recording.

SDNN: the standard deviation of the normal (NN) sinus-initiated IBI measured in milliseconds.

SDNN index (SDNNI): the mean of the standard deviations of all the NN intervals for each 5-minute segment of a 24-hour HRV recording.

SDRR: the standard deviation of the interbeat interval for all sinus beats measured in milliseconds, which predicts both morbidity and mortality.

triangular Interpolation of the NN Interval Histogram (TINN): the baseline width of a histogram displaying NN intervals.

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, identify the index that is the "gold standard" for predicting the risk of morbidity and mortality when based on 24-hour recording. Which index should be most easily understood by your clients? Why?

References

Andreassi, J. L. (2000). Psychophysiology: Human behavior and physiological response. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc.

Berntson, G. G., Quigley, K. S., & Lozano, D. (2007). Cardiovascular psychophysiology. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.). Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Billman, G. E., Schwartz, P. J., & Stone, H. L. (1982). Baroreceptor reflex control of heart rate: A predictor of sudden cardiac death. Circulation, 66(4), 874-80. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.66.4.874

Booiman, A. (2017). Personal communication regarding HR Max-HR Min slow-paced breathing in the Netherlands.

Burr, R. L., Motzer, S. A., Chen, W., Cowan, M. J., Shulman, R. J., & Heitkemper, M. M. (2006). Heart rate variability and 24-hour minimum heart rate. Biol Res Nurs, 7(4), 256-267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800405285268

Ciccone, A. B., Siedlik, J. A., Wecht, J. M., Deckert, J. A., Nguyen, N. D., & Weir, J. P. (2017). Reminder: RMSSD and SD1 are identical heart rate variability metrics. Muscle Nerve. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25573

Combatalade, D. (2010). Basics of heart rate variability applied to psychophysiology. Thought Technology Ltd.

DeGiorgio, C. M., Miller, P., Meymandi, S., Chin, A., Epps, J., Gordon, S., Gornbein, J., & Harper, R. M. (2010). RMSSD, a measure of vagus-mediated heart rate variability, is associated with risk factors for SUDEP: The SUDEP-7 Inventory. Epilepsy Behav, 19(1), 78-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.06.011

Gevirtz, R. N. (2017). Cardio-respiratory psychophysiology: Gateway to mind-body medicine.

Hämmerle, P., Eick, C., Blum, S., Schlageter, V., Bauer, A., Rizas, K. D., . . . Swiss‐AF Study Investigators (2020). Heart rate variability triangular index as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(15). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.016075

Hill, L. K., & Siebenbrock, A. Are all measures created equal? Heart rate variability and respiration – biomed 2009. Biomed Sci Instrum, 45, 71-76. PMID: 19369742

Jarczok, M. N., Koenig, J., & Thayer, J. F. (2021). Lower values of a novel index of vagal-neuroimmunomodulation are associated to higher all-cause mortality in two large general population samples with 18 year follow up. Sci Rep, 11, 2554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82168-6

Jovic, A., & Bogunovic, N. (2011). Electrocardiogram analysis using a combination of statistical, geometric, and nonlinear heart rate variability features. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 51, 175-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2010.09.005

Kleiger, R. E., Miller, J. P., Bigger, J. T., & Moss, A. J. (1987). Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. American Journal of Cardiology, 59, 256-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(87)90795-8

Lehrer, P. M. (2007). Biofeedback training to increase heart rate variability. In P. M. Lehrer, R. M. Woolfolk, & W. E. Sime (Eds.). Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Lehrer, P. M. (2012). Personal communication.

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., & Vaschillo, B. (2000). Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: Rationale and manual for training. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25(3), 177-191. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009554825745

Nunan, D., Sandercock, G. R. H., & Brodie, D. A. (2010). A quantitative systematic review of normal values for short-term heart rate variability in healthy adults. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 33(11), 1407-1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02841.x

Pentillä, J., Helminen, A., Jarti, T., Kuusela, T., Huikuri, H. V., Tulppo, M. P., . . . Scheinin, H. (2001). Time domain, geometrical and frequency domain analysis of cardiac vagal outflow: effects of various respiratory patterns. Clin Phys, 21, 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2281.2001.00337.x

Schipke, J. D., Arnold, G., and Pelzer, M. (1999). Effect of respiration rate on short-term heart rate variability. J. Clin Basic Cardiol. 2, 92–95.

Schwartz, P. J., Vanoil, E., Stramba-Badiale, M., De Ferrarie, G. M., Billman, G. E., & Foreman, R. D. (1988). Autonomic mechanisms and sudden death. New insights from analysis of baroreceptor reflexes in conscious dogs with and without a myocardial infarction. Circulation, 78(4), 969-79. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.78.4.969

Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258

Shaffer, F., McCraty, R., & Zerr, C. L. (2014). A healthy heart is not a metronome: An integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01040

Shaffer, F., Meehan, Z. M., & Zerr, C. L. (2020). Frontiers in Neuroscience. A critical review of ultra-short-term heart rate variability norms research. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.594880

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (1996). Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation, 93, 1043-1065. PMID: 8598068

Tarvainen, M. P., & Niskanen, J.-P. (2017). Kubios HRV version 3.0 user's guide. University of Finland.

Umetani, K., Singer, D. H., McCraty, R., & Atkinson, M. (1998). Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: Relations to age and gender over nine decades. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 31(2), 593-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00554-8

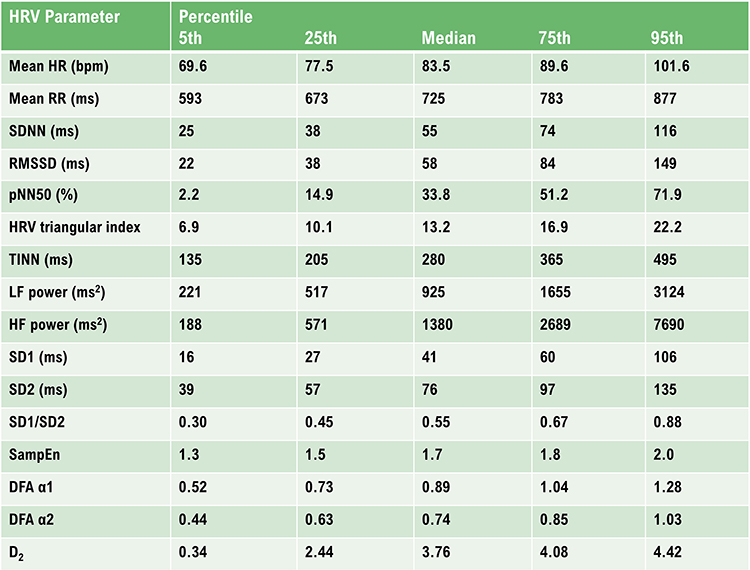

Zerr, C., Kane, A., Vodopest, T., Allen, J., Fluty, E., Gregory, J., . . ., & Shaffer, F. (2014). Heart rate variability norms for healthy undergraduates [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 39(3), 300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-014-9254-9

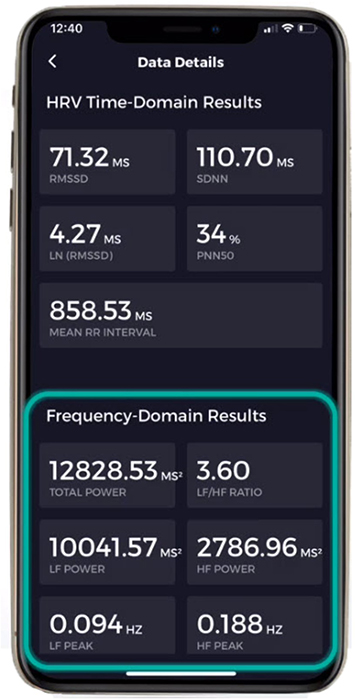

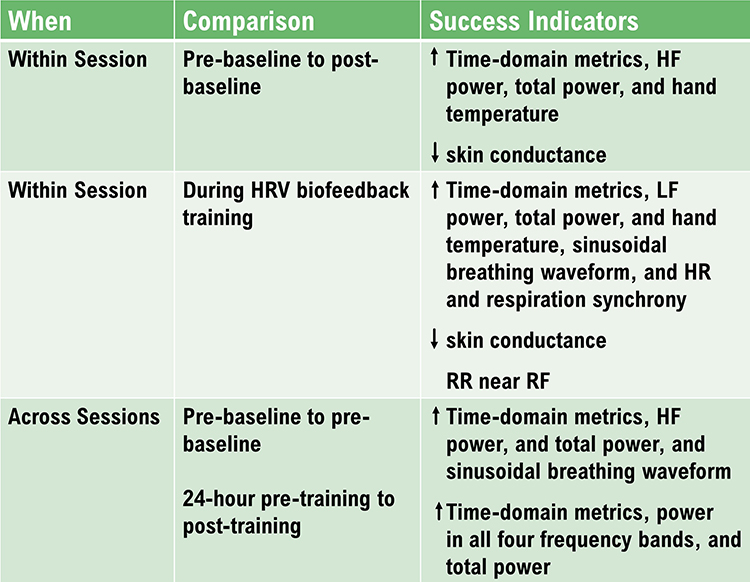

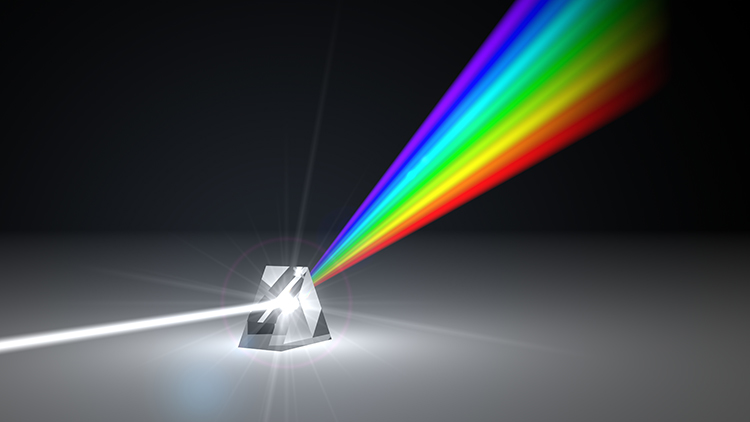

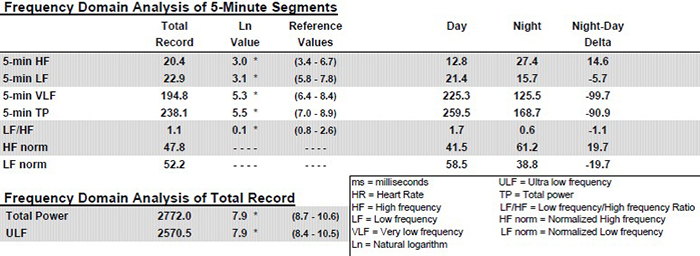

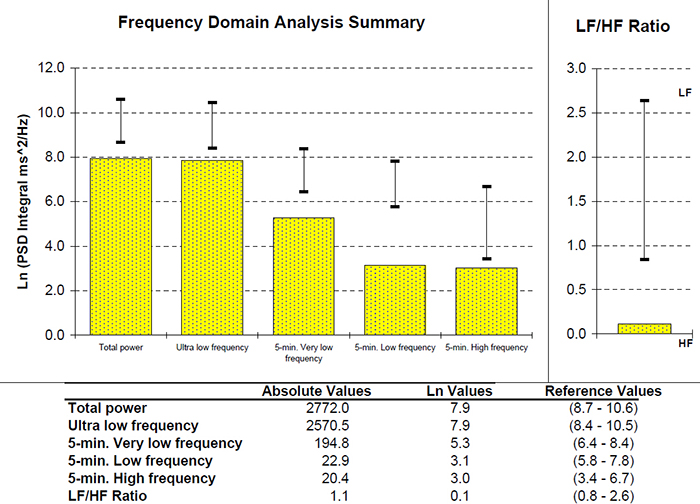

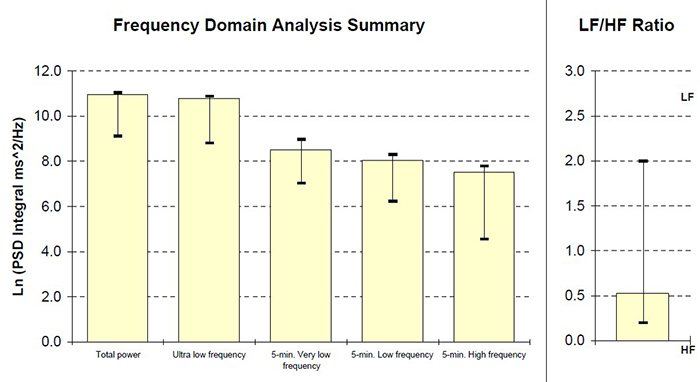

C. HRV FREQUENCY-DOMAIN MEASUREMENTS

HRV frequency-domain measurements reveal the sources of physiological changes and play an integral role in heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB).

We train clients to increase LF power in the clinic to enhance vagal tone and HF power when they breathe at typical rates in everyday life (Gevirtz, 2020).

Listen to a mini-lecture on HRV Frequency-Domain Metrics © BioSource Software LLC.

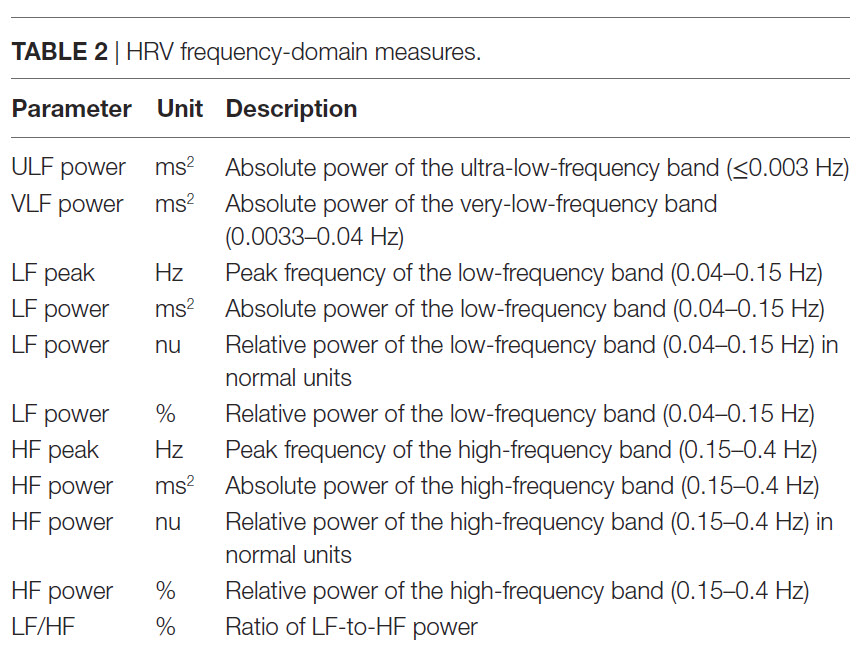

Where time-domain indices quantify the total amount of heart rate variability (HRV), frequency-domain measurements quantify absolute or relative power distribution into four frequency bands.

Analogous to the electroencephalogram (EEG), we can use power spectral analysis or autoregressive (AR) modeling to separate HRV into its component rhythms. Each rhythm operates within a different frequency range. This is analogous to a prism that refracts light into its component wavelengths. Graphic © kmls/Shutterstock.com.

Review this post to learn more about Fast Fourier power spectral analysis.

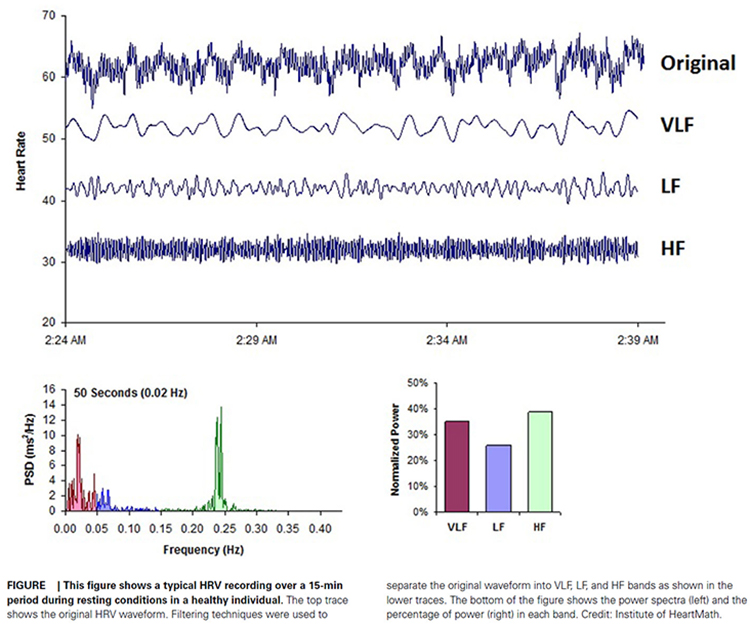

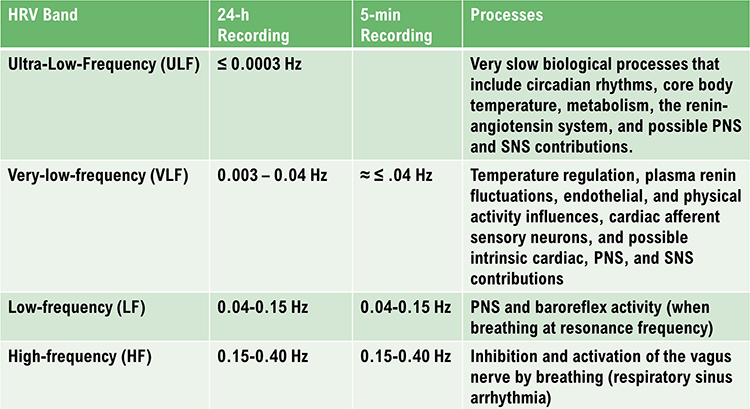

The Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (1996) divided heart rate oscillations into four frequency bands. The VLF, LF, and HF bands are shown below.

This section covers the ULF, VLF, LF, and HF Bands, minimum recording periods, and the controversial LF/HF ratio.

Perspective on Frequency-Domain Measurements

The processes that contribute to HRV operate at different speeds and therefore generate different frequencies. Frequency-domain measurements quantify the absolute or relative amount of HRV signal power within each of four frequency bands (ultra-low, very-low-frequency, low-frequency, and high-frequency).

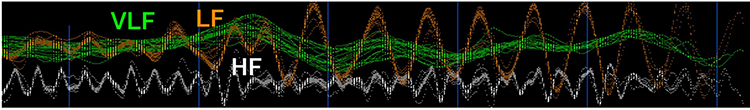

In the graphic below that is courtesy of Dick Gevirtz, very-low-frequency activity is green, low-frequency activity is orange, and high-frequency activity is white.

We express absolute power in ms squared divided by cycles per second (ms2/Hz). Relative power is a frequency band’s percentage of total HRV power. We can express this in normal units (nu) by dividing the absolute power for a specific frequency band by the summed absolute power of the low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF) bands.

While normal units allow us to compare the spectral distribution in two clients directly, they conceal the actual contributions of each frequency band to HRV (Gevirtz, 2020). Journals now prefer the natural logs of LF and HF power. A natural log expresses a value to the base e. The irrational mathematical constant e ≈ 2.71828.

The autonomic contribution to the ultra-low-frequency (ULF), very-low-frequency (VLF), and low-frequency (LF) bands remains controversial since measurements profoundly vary with testing conditions (Lehrer, 2012).

Ultra-Low-Frequency Band

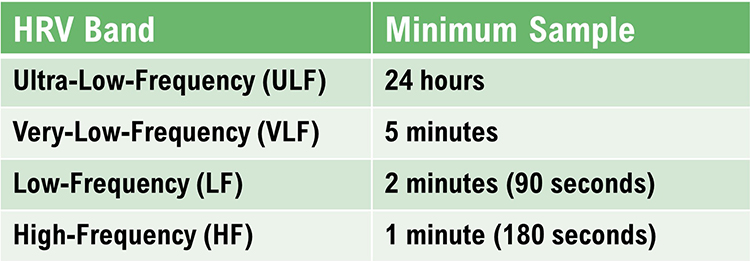

The ultra-low-frequency (ULF) band (≤ 0.003 Hz) indexes fluctuations in interbeat intervals with a period from 5 minutes to 24 hours and is measured using 24-hour recordings (Kleiger et al., 2005). Due to its long cycle length (> 5 hours), ULF activity is too gradual to train using conventional biofeedback (Stauss, 2003).

ULF Sources

There is no consensus regarding the mechanisms that generate ULF power. Very slow-acting biological processes are implicated. Circadian rhythms may be the primary driver of this rhythm (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014). Core body temperature, metabolism, and the renin-angiotensin system operate over a long period and may also contribute to these frequencies (Task Force, 1996; Bonaduce et al., 1994). Different psychiatric disorders show distinct circadian patterns in 24-hour heart rates, particularly during sleep (Stampfer, 1998; Stampfer & Dimmitt, 2013). There is disagreement about the contribution of the PNS and SNS to this band. Due to its long cycle length (> 5 hours), ULF activity is too gradual to train using conventional biofeedback (Stauss, 2003).ULF Correlates

ULF power is highly correlated with the SDANN time-domain index (Bigger et al., 1992).Very-Low-Frequency Band

The very-low-frequency (VLF) band (0.0033-0.04 Hz) comprises rhythms with periods between 25 and 300 seconds. VLF measurement requires a recording period of at least 5 minutes but may be best monitored over 24 hours (Task Force, 1996). In the FFT spectral plot, VLF power is colored gray.

VLF Sources

There is uncertainty regarding the physiological mechanisms responsible for activity within this band (Kleiger et al., 2005). The heart's intrinsic nervous system appears to contribute to the VLF rhythm, and the SNS influences the amplitude and frequency of its oscillations (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).VLF power may also be generated by physical activity (Bernardi et al., 1996), thermoregulatory, renin-angiotensin, and endothelial influences on the heart (Akselrod et al., 1981; Claydon & Krassioukov, 2008). There may be an alpha-adrenergic (norepinephrine-mediated) vascular tone contribution (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2021). PNS activity may contribute to VLF power since parasympathetic blockade almost completely abolishes it (Taylor et al., 1998). In contrast, sympathetic blockade does not affect VLF power, and VLF activity is seen in tetraplegics, whose SNS innervation of the heart and lungs is disrupted (Task Force, 1996; Berntson et al., 1997).

Based on work by Armour (2003) and Kember et al. (2000, 2001), the VLF rhythm appears to be generated by the stimulation of afferent sensory neurons in the heart. This, in turn, activates various levels of the feedback and feed-forward loops in the heart's intrinsic cardiac nervous system, as well as between the heart, the extrinsic cardiac ganglia, and the spinal column.

Dr. Lehrer explains the VLF band © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. You can enlarge the video by clicking on the bracket icon at the bottom right of the screen. When finished, click on the ESC key.

VLF Correlates

While all low values on all 24-hour clinical HRV measurements predict a greater risk of adverse outcomes, VLF power is more strongly associated with all-cause mortality than LF or HF power (Tsuji et al., 1994, 1996; Hadase et al., 2004; Schmidt et al., 2005). The VLF rhythm may be fundamental to health (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).Low VLF power is associated with arrhythmic death (Bigger et al., 1992) and PTSD (Shah et al., 2013). Low power in this band has been associated with high inflammation in several studies (Carney et al., 2007; Lampert et al., 2008).

Finally, low VLF power has been correlated with low testosterone levels, while other biochemical markers, such as those mediated by the HPA axis (e.g., cortisol), did not (Theorell et al., 2007). VLF power is strongly correlated with the SDNN index time domain measure, which averages 5-minute standard deviations for all NN intervals over 24 hours.

Significance for HRV Biofeedback

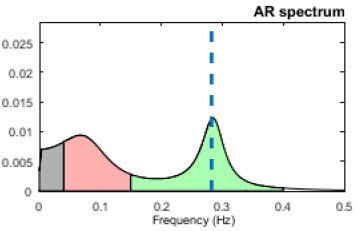

VLF elevations may signal chronic SNS activation or vagal withdrawal (parasympathetic suppression) due to chronic worry or excessive effort during training (Gevirtz, 2017).Low-Frequency Band

The low-frequency (LF) band (0.04-0.15 Hz) is comprised of rhythms with periods between 7 and 25 seconds, is affected by breathing from ~3-9 breaths per minute (bpm), and requires a recording period of at least 2 minutes (Task Force, 1996). The baroreflex system’s resonance falls within the LF band. This region was previously called the baroreceptor range because it reflects baroreceptor activity during resting conditions (McCraty & Shaffer, 2015). In the FFT spectral plot, LF power is colored orange.

LF Sources

While there is disagreement regarding this band's activity sources, a sympathetic role during resting measurements appears unlikely (Hayano & Yuda, 2019). The PNS and blood pressure regulation may produce LF power via baroreceptors (Akselrod et al., 1981; Berntson, Quigley, & Lozano, 2007; Lehrer, 2007; Task Force, 1996) or by baroreflex activity alone (Goldstein et al., 2011). The late Evgeny Vaschillo studied a possible SNS component near 0.05 Hz (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2021). Breathing at rates below 8.5 breaths per minute, sighing, and taking deep breaths may contribute to LF activity via the vagus (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).Dr. Lehrer explains the LF band © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Significance for HRV Biofeedback

Use LF band power to assess the success of HRVB when your client breathes from 4.5-7.5 bpm (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). Expect elevated LF during resonance frequency (RF) breathing. High LF at typical breathing rates (e.g., 12-14 bpm) signals that the vagal brake is malfunctioning (Khazan, 2020).A single high amplitude peak near 0.1 Hz indicates high coherence within the Institute of HeartMath model.

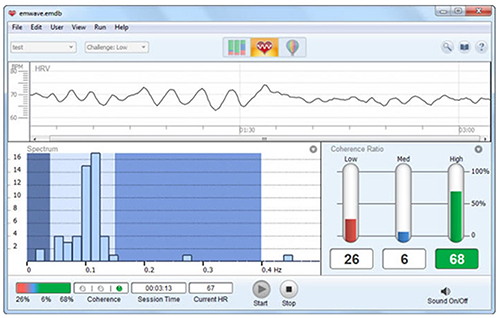

Caption: The Institute of HeartMath display shows instantaneous HR at the top. The bottom left features a HRV spectral display. Note that there are two peaks around 0.1 Hz instead of one. The bottom right shows coherence ratios. Note that the individual has only achieved 68% high coherence at the low challenge level.

Coherence is a proprietary HeartMath term that means a "narrow, high-amplitude, easily visualized peak" from 0.09-0.14 Hz (Ginsberg, Berry, & Power, 2010, p. 54).High-Frequency (HF) Band

The high-frequency (HF) or respiratory band (0.15-0.40 Hz) is influenced by breathing from 9-24 bpm (Malik, 1996) and requires a recording period of at least 1 minute. For infants and children, who breathe faster than adults, the resting range can be adjusted to 0.24-1.04 Hz (Quintana et al., 2016).

HF Sources

The HF band reflects parasympathetic activity and is called the respiratory band because it corresponds to the HR variations related to the respiratory cycle. These phasic HR changes are known as respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) and may not be a pure index of cardiac vagal control (Grossman & Taylor, 2007).Recall that HR accelerates during inspiration and slows during expiration. During inhalation, the cardiovascular center inhibits vagal outflow, speeding the heart rate. Conversely, during exhalation, it restores vagal tone, slowing the heart rate via the release of acetylcholine (Eckberg & Eckberg, 1982).

Total vagal blockage virtually eliminates HF oscillations and reduces power in the LF range (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

Dr. Lehrer explains the HF band © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

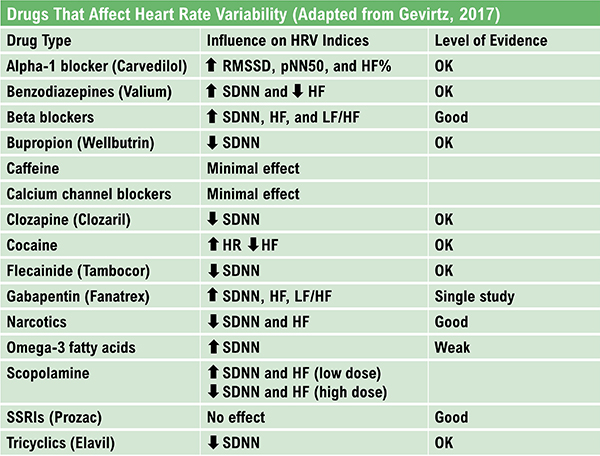

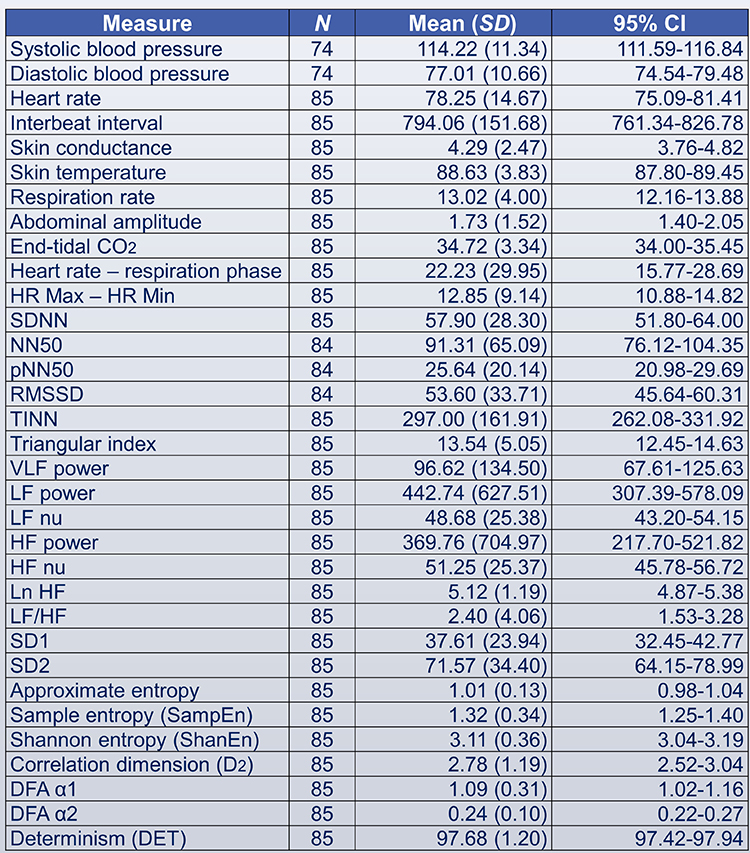

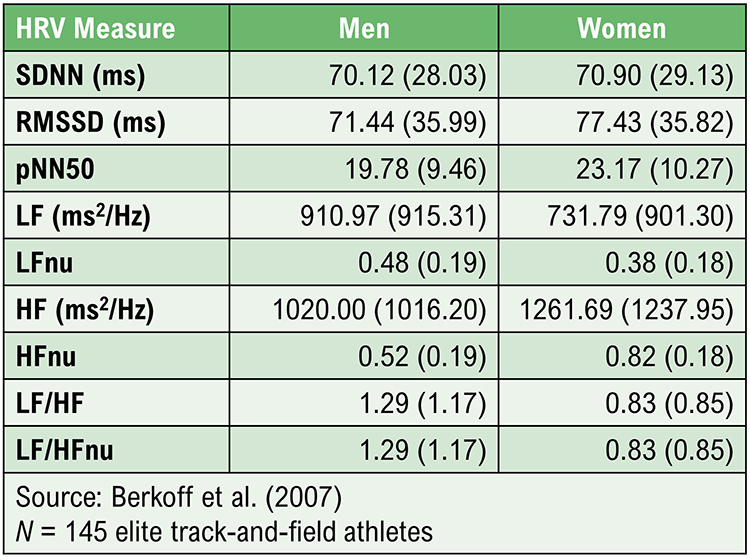

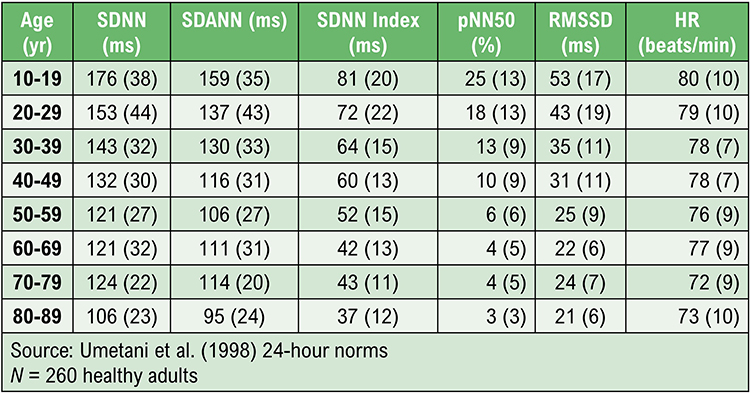

HF Correlates